Surviving hate, spreading hope

By April Miller, assistant director of communications and Michelle Joyce-Fyffe, director of regional engagement

Evelyn Diamont Banko, BA ’57 (elementary education) and the parents of Rob Aigner, BS ’86 (journalism) are Holocaust survivors. The two alumni share their families’ stories of hardship, resilience, and hope.

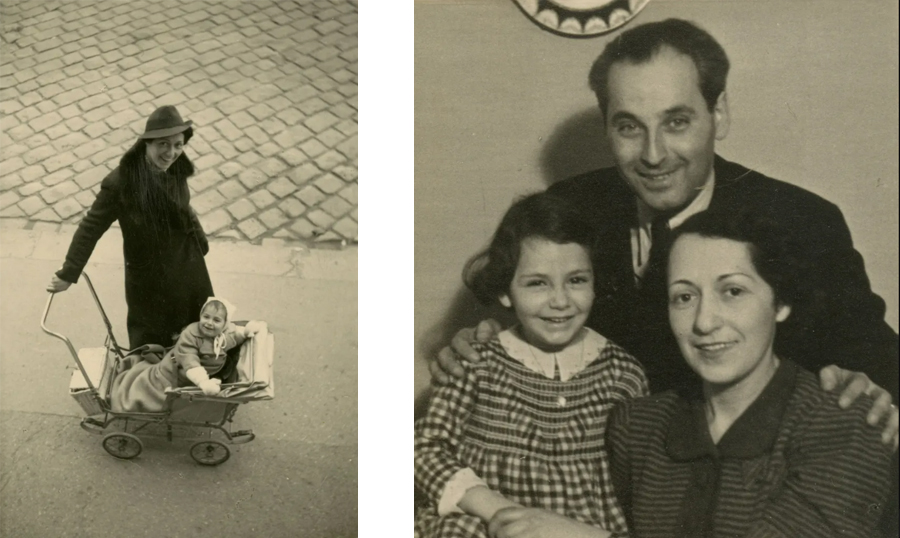

Evelyn's parents, Frieda and Joseph Diamont, in Vienna prior to the war. Credit: OJMCHE Archives

Evelyn Diamont Banko, BA ’57 (elementary education)

Growing up in Portland, Evelyn Diamont Banko, BA ’57 (elementary education) at times felt she was living a double life. Outside of the home she shared with her parents, she spoke little of her Jewish heritage or her family’s harrowing escape from Vienna after the Nazi annexation of Austria.

“My parents were so afraid of antisemitism when we got to the United States,” Banko said. “Most of my neighbors were Catholic. I went to a school where there were no other Jewish children, so my parents just decided there was no need to tell anybody we were Jewish.”

At school and among her friends, Banko just wanted to feel like a typical American kid. And having immigrated to the US at just four years old, she was. However, her family’s journey to the life they’d enjoy in Portland looked very different from most of Banko’s peers.

In March 1938, when Banko was two years old, Nazi troops entered her birthplace of Vienna, and all anti-Jewish decrees that had been issued in Germany since 1933 became law in Austria. Banko’s father Joseph Diamont, an engineer and business owner, began trying to figure out how to get himself, his wife Frieda, and young Evelyn out of the country.

Pictured left: Evelyn Banko with her mother Frieda on a walk in Vienna. Pictured right: Joseph, Frieda, and Evelyn sit for a family portrait before leaving Vienna. Photo Credit: Oregon Jewish Museum and Center for Holocaust Education Archives

A few months later in August 1938, as Diamont was walking to work, a Nazi who sympathized with him warned him not to return home that night, or he would be arrested and likely taken to a work camp. Banko’s father heeded the man’s warning, and five days later, the Diamont family fled to Riga, Latvia, where they would live for two years until the Russian invasion.

“My parents took this class on how to make belts and purses, and that’s what we did the two years that we were in Latvia,” Banko said. “Riga was one of the few places that you could go without papers. The whole time that we were there, we were trying to get to the United States.”

Immigrating to the United States was no easy feat though. It required an affidavit of financial support from someone living in the US, and during the Great Depression, this was not something many Americans could afford. The Diamonts didn’t have many relatives in the US but were fortunately able to receive an affidavit from the employer of a distant relative. The family was granted permission to leave Latvia in June 1940 and were three out of 1,500 people allowed to do so.

“After we left the port, we went through a storm. The boat was rocking, and everybody was seasick. But all my father remembered about it is that they had the most beautiful view of Mount Fuji, and it was just gorgeous,” Banko said laughing. “My dad loved nature and beautiful things. He always looked for the silver lining; both my parents did.”

Through the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society, Banko’s father was put in charge of the twenty-four Jewish refugees who were on the train. The group took the Trans-Siberian Railroad across Russia to Manchuria, China and on to Kobe, Japan, where they boarded a ship for Seattle.

“After we left the port, we went through a storm. The boat was rocking, and everybody was seasick. But all my father remembered about it is that they had the most beautiful view of Mount Fuji, and it was just gorgeous,” Banko said laughing. “My dad loved nature and beautiful things. He always looked for the silver lining; both my parents did.”

After about six weeks of travel from Riga to Seattle, Banko’s family and the other refugees arrived in the US. They were given the choice of going to Portland or San Francisco. Her parents chose Portland because it was a smaller city, and the Cascades reminded them of the mountains near Vienna.

Joseph Diamont at his Texaco Station at SE 17th and Holgate, c. 1945. Photo Credit: OJMCHE Archives

Her mother found work as a seamstress at Hirsch-Weis. Her father temporarily found work as a janitor until he got a job managing a Texaco service station in SE Portland. Her family quickly found community among other German-speaking Jewish immigrants, several whom Banko considered her family while she was growing up. Among them were the Fells—a couple and their daughter Alice—who the Diamonts had met on the Trans-Siberian train.

“I didn’t remember my family because I’d left Austria at two, so my parents’ friends became my aunts and uncles,” Banko said. “Alice and I have been friends our whole life, and we’re like sisters. We grew up together, both of us with no relatives.”

“My mother tried to go to a synagogue once in Portland, after she became aware of what probably had happened to her relatives. She walked into the synagogue, and she said all she saw were the faces of her dead relatives, and she just could never go back again.”

Many of Banko’s relatives, including her uncle, aunt, and grandparents were murdered by the Nazis in the Holocaust. When she and her children and grandchildren visited Vienna last year, they counted at least twenty-two relatives’ names in the “Shoah Wall of Names,” a new memorial which was inaugurated in December 2022.

Evelyn Banko pictured with her family during a trip to Vienna in 2022.

After attending preschool through high school in Portland, Banko moved to Eugene in 1953 to attend the University of Oregon, where she studied elementary education. She joined a sorority at the UO, which she said likely wouldn’t have been allowed at the time, had the parent organization known she was Jewish.

After graduating in 1957, Banko returned to Portland, where she earned a master’s degree and worked as an educator for thirty-three years. In 1958, she married her late husband, Richard Banko, with whom she raised two children.

Evelyn Banko pictured at her 60th Reunion in 2017 alongside The Duck and other reunion attendees.

It was toward the end of her career that Banko decided to begin speaking about her life and experiences as a Holocaust survivor through an Anne Frank exhibit that was temporarily set up in Portland. Today, she continues to speak as a volunteer with the Oregon Jewish Museum and Center for Holocaust Education, and she is a docent guiding tours at the Holocaust Memorial in Washington Park.

Banko has visited hundreds of schools in Oregon and SW Washington to share her parents’ experiences before and during the Holocaust. She speaks to classrooms of students and big groups during assemblies. She also speaks at businesses and churches.

“I just feel it’s so important that children hear our stories and hear what happened to get a true feeling of what was going on in Europe at that time and how it’s similar to things that are going on around the world nowadays,” Banko said. “We can see patterns in history and in modern day life in which minority populations get blamed for the problems in society. It’s important for people of all ages to understand that bullying and exclusion can lead to things as big as the Holocaust. They need to be aware when these things happen to call it out and push against the tide of hatred.”

—By April Miller, assistant director of marketing and communications

Rob Aigner, BS ’86 (journalism)

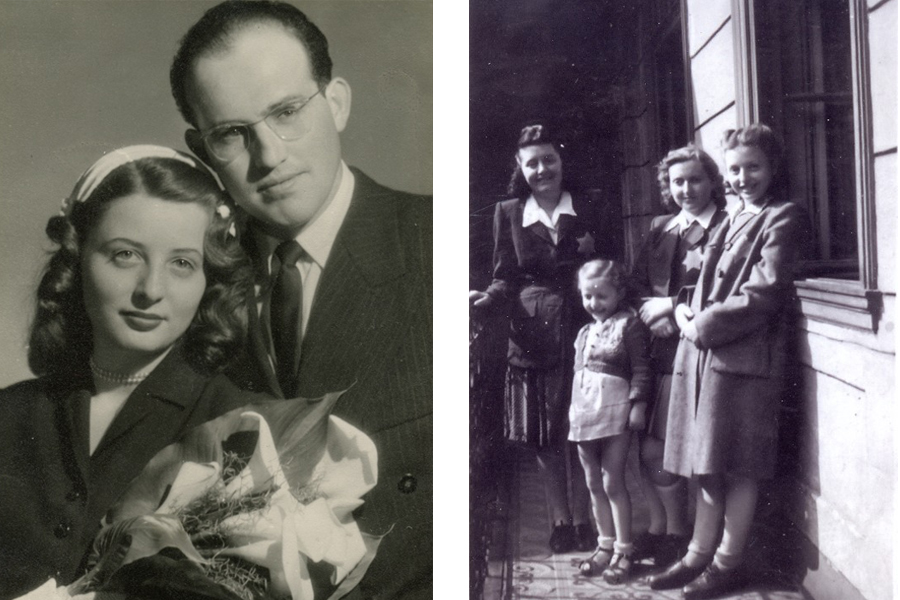

Les Aigner (standing) with his mother and sisters

Rob Aigner’s parents never talked about their experiences surviving the Holocaust, when he and his sister Sue were growing up in suburban Portland.

It wasn’t until a high school history class sparked his interest in the subject that Aigner, a 1986 UO graduate, asked what had happened to them in Nazi-occupied Europe.

“They were incredibly reluctant to talk about it,” he said. “They didn’t want to have anything to do with the conversation.”

But when Holocaust deniers started spreading their message of hate across America in the ’80s and early ’90s, Aigner said his parents could no longer stay silent.

“For the first time, I saw my dad get really impassioned about this subject,” Aigner said. “My mom and dad decided that they had to talk, they had to do something.”

It took years for Les and Eva Aigner to open up and share their tragic family history, even with their own children.

Pictured left: Les and Eva Aigner on their wedding day in Budapest in 1956. Pictured right: Eva Aigner pictured with family members and forced to wear the yellow star. Photo Credit left: OJMCHE archives. Photo Credit right: Rob Aigner.

Les was taken to Auschwitz with his mother, Anna, and eight-year-old sister Marie, who were both murdered in the gas chambers. Then he was sent to Dachau on the so-called “Death Train” before American troops liberated the camp on April 29, 1945, a date he called his “second birthday.”

Eva narrowly escaped a Nazi firing squad, after her mother, Gisella, bribed a guard with her wedding ring.

They’ve told their story to hundreds of thousands of people in the years since—from appearances on PBS to lectures at universities and high schools across the state. They testified before the Oregon Senate Committee on Education in support of a bill that was signed into law by Gov. Kate Brown in 2019, making Holocaust teaching mandatory in the state’s public schools.

“My parents are literally my heroes,” Aigner said. “There’s an obligation on our entire family to carry on this history, to make sure it’s not forgotten.”

Now in her eighties and with Les having passed away in 2021, Eva doesn’t give public talks often anymore, but Aigner said he wanted to keep alive his parents’ message: Never give up, you’re stronger than you think.

“My parents are literally my heroes,” Aigner said. “There’s an obligation on our entire family to carry on this history, to make sure it’s not forgotten.”

Eva and Les Aigner pose in front of panels containing their photos, which were produced by the Oregon Jewish Museum and Center for Holocaust Education. Photo credit: Rob Aigner

Aigner, who earned a bachelor’s degree in journalism in 1986, said his parents’ story also inspired him to start a podcast called “Clear Choices,” where he interviews people who’ve turned hardship and adversity into motivation for creating better lives and improving their community.

And there’s a final lesson that Aigner said he learned from his mother: the importance of education.

“Discrimination can start with little things,” Eva Aigner said in an interview with the Oregon Jewish Museum and Center for Holocaust Education. “The way to fight is to educate the young people. To let them know what discrimination can do.”

—By Michelle Joyce-Fyffe, director of regional engagement