Honoring Black History Month

By April Miller, UO Alumni Association assistant director of marketing and communications

This Black History Month, we celebrate and reflect on the contributions of Black Americans to American history, Oregon history, and UO history.

February is Black History Month, a time to celebrate the countless contributions, achievements, and culture of African Americans who have influenced and formed American history. It’s also a time to reflect on the struggles and injustices Black Americans have faced and the systemic inequities with lasting impacts today. Black History Month has been officially recognized nationwide since 1976.

As an historically White state and institution, Oregon has a racist history that shaped the state and university’s racial diversity and treatment of Black Americans. Oregon’s first Black exclusion laws were passed in 1844 and were not officially removed from the state constitution until 1926. Nearly a century later, only about 2% of the state’s population is African American.

In the face of injustices and barriers rooted in systemic racism, Black students, alumni, faculty, and staff have continued to show up, build community, exude joy, and make an incredible impact at the University of Oregon.

In this article, we highlight a few of these UO community members, but there are numerous others who have strengthened the campus community over the decades. This month and every month, the UO Alumni Association wishes to recognize and honor all Black alumni, faculty, staff, and friends for who they are and all they contribute to the Ducks community.

3,592

UO alumni identifying as Black/African American

633

current students identifying as African American

2.66%

percentage of UO student body identifying as African American

Black Ducks Who've Made a Difference

The Black Ducks featured below have contributed meaningfully to the university and our surrounding community, often in the face of racism and discrimination. This list includes individuals both living and deceased, as we wish to honor the legacy of those who have gone before us and paved a way for current and future Black Ducks. Not every African American individual who has made a difference at the UO is on this list, but we hope it will underscore the many achievements of Black UO alumni from music to activism, sports to literature, and so much more.

Nellie Franklin, BA ’32 (music)

Nellie Louise Franklin made history when she graduated from the University of Oregon in 1932, becoming the first African American woman on record to do so. She faced discrimination throughout her time at the UO, but showed incredible resilience in the face of this treatment, earning a music degree four years after arriving in Eugene.

Franklin’s family moved to the Pacific Northwest in 1915, after Nellie’s father, Sergeant Alfred Franklin, finished a distinguished military career. The family landed in Fort Vancouver, Washington, but faced racial segregation and were forced to relocate to Northeast Portland, a vibrant African American community. Franklin attended Washington High School and was a talented musician at Bethel African American Episcopal Church.

Following her high school graduation, Franklin continued her education at the UO. She faced housing discrimination and was not allowed to live in on-campus dormitories. Despite being forced to live off campus, she became involved in several student organizations, including the Women’s Athletic Association, Cosmopolitan Club, and Polyphonic Choir. Franklin wanted to join a sorority as well, but faced discrimination in Greek life, which was restricted to White students at the time.

Determined to ensure future generations of Black women in the Pacific Northwest have access to sorority life, Franklin was one of several women in Oregon and Washington to first advocate for a Black sorority in the region. This advocacy effort after her graduation from the UO created a lasting legacy for Black women in higher education spaces for many years to come.

Much of what we know about Franklin is thanks to the work of UO alumnus Herman Brame, BS ’68 (sociology), who has documented Black history at the university, publishing “Nellie L. Franklin: Pioneering Oregon Soror” in 2015.

Read more about Nellie Franklin

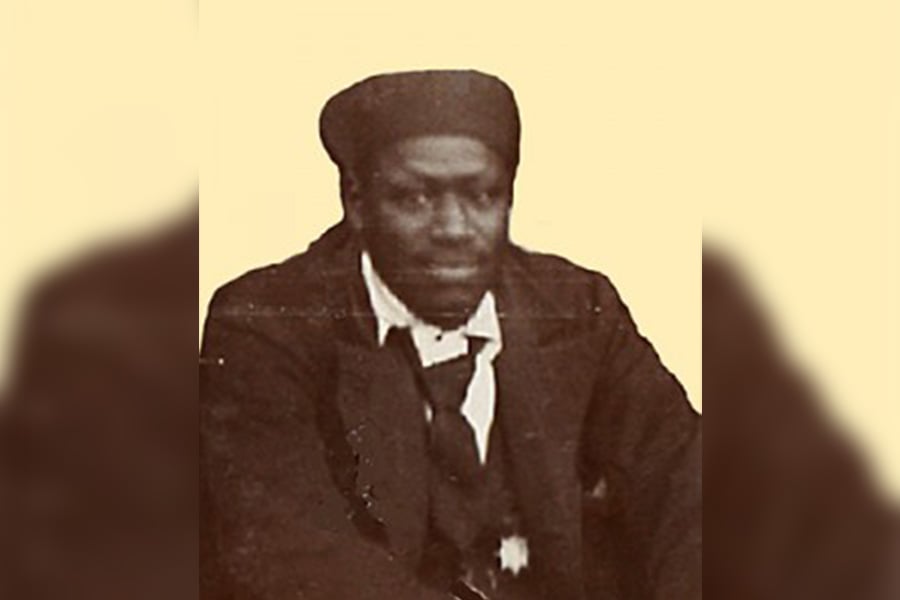

Wiley Griffon

Wiley Griffon was the first African American employee at the UO, where he worked as a janitor in Friendly Hall in the late 1890s. The building is now home to the School of Global Studies and Languages, but after its construction in 1893, housed a men’s dormitory.

Oregon’s Black exclusion laws forbade African Americans from entering or settling in the territory and the community was prejudiced against Black residents. However, Griffon made Eugene his home anyway, moving from Texas.

Prior to his stint at the UO, Griffon worked as the driver for Eugene’s first streetcar service, powered by a mule. He worked several other jobs in the community, including as a waiter on a railroad dining car and at the Elks Club. In 1909, he purchased a home along the Willamette River, on the site of what is now the EWEB parking lot.

Griffon is buried in the Eugene Masonic Cemetery, but his tombstone went missing. Community members came together to raise funds for an historic monument and plaques at the Lane Transit District and Eugene Water and Electric Board offices.

Read more about Wiley Griffon

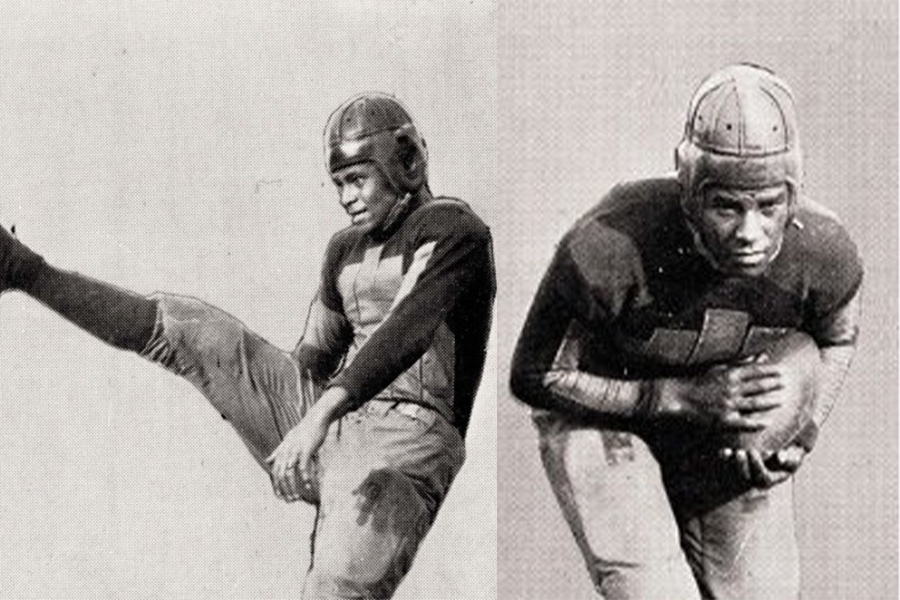

Bobby Robinson, BA ’35 (physical education) & Charles Williams, class of 1930

Robert “Bobby” Robinson and Charles Williams were the first two African American athletes to compete at the University of Oregon. The Portland natives were offered full scholarships and recruited by head Oregon football coach John J. McEwan. They came to Eugene in 1926, the same year Oregon finally repealed its Black exclusion law.

When Robinson and Williams arrived to campus to continue their education and play for the Webfoots, they were disallowed from living in the “Whites only” on-campus dorms and forced to live off-campus. However, their White teammates signed a petition and submitted it to the university, demanding Robins and Williams be allowed to live in the on-campus dormitories with them. By their sophomore year, the university relented, but required that the two occupy a living space separate from the team and enter the building from their own entrance.

On the football field, both Robinson and Williams proved to be key athletes on the roster. Both men played a variety of positions, with Robinson at quarterback for a time. By the 1928 season, they were both full-time on the backfield and alongside quarterback John Kitzmiller, led Oregon to its first-ever nine-season win.

Despite their successes, Robinson and Williams continued to face discrimination, with many boosters and community members objecting to the two being on the field at the same time. Coach McEwan begrudgingly made a compromise not to start both Robinson and Williams when the team played at home in Eugene or in Portland. To make matters worse, the duo was left out of the last game of their senior season against the University of Florida, which had a strict policy in place: no Black athletes allowed. The UO administration reluctantly agreed to leave Robinson and Williams behind—a disappointment to the pair and an outrage to many Oregon fans.

Robinson went on to live in Los Angeles for several years and to compete in pole-vault in Canada, prior to returning to the UO to get his degree in physical education in 1935. He settled down in LA where he later became a social activist. Williams returned to Portland where he married and served Oregonians by working for the state for more than three decades.

Read more about Bobby Robinson and Charles Williams

Mabel Byrd, class of 1921 (economics)

Mabel Byrd was the first African American student to enroll at the University of Oregon. After graduating from Portland’s Washington High School as the only Black student in her class, she moved to Eugene, where she would face similar isolation.

Byrd matriculated at the UO in 1917 as an economics major and spent two years at the university. State exclusion laws and school policy prohibited her from living in on-campus dorms, so she lived in the home of history professor Joseph Schafer, for whose family she worked as a domestic servant. In 1919, Byrd transferred to the University of Washington, where she earned a BA in liberal arts.

Post-grad, she was an activist in the Civil Rights movement, working alongside national leaders like W.E.B. DuBois, and supported national and international organizations such as YWCA, NAACP, and the League of Nations. Byrd later worked at Fisk University in Nashville, where she investigated conditions in segregated schools; worked toward implementing codes to improve employment opportunities and equal pay for African Americans related to Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal; and served as the executive director of the People’s Art Center in St. Louis.

Read more about Mabel Byrd

DeNorval Unthank Jr., BArch ’52 (architechure)

If you’ve visited the UO’s Eugene campus recently, you may be familiar with one of the university’s newest residence halls—DeNorval Unthank Jr. Hall. However, depsite Unthank’s impressive architecture career and many contributions to the UO, many Ducks had never heard his name until a few years ago.

Unthank transferred to the University of Oregon as a junior, becoming the first African American to graduate from the UO’s architecture program in 1952. The son of one of Portland’s first practicing Black physicians, Unthank came from a progressive and accomplished family.

Like several other alumni represented in this feature, Unthank was not allowed to live in on-campus housing during his time as a student. He was threatened with violence for dating a White woman, Deb Mohr, who would later become his first wife. In May 1951, Ku Klux Klan members lit a cross on fire on the lawn of the Gamma Phi Beta sorority house, where Mohr lived. She later told an account of sorority and UO leaders asking her to stop seeing Unthank. When the couple decided to wed, they had to go to Vancouver, Washington because interracial marriages were still outlawed in Oregon at the time.

Despite facing countless racist attacks, Unthank persevered to earn his degree and immediately launched into a professional career, setting roots in Lane County. He partnered with local construction magnate Richard Chambers to build houses in south Eugene, and by 1968, co-founded Unthank Seder Poticha Architects. He designed several notable buildings throughout Lane County, including the UO’s McKenzie Hall, the Lane County Courthouse, and Thurston High School in Springfield. Unthank also served as an associate professor with the UO School of Architecture and Allied Arts, now the College of Design, for more than 15 years.

It would be years after his death in 2000 before the university would recognize Unthank for his outstanding accomplishments. It started, when in fall 2015, the Black Student Task Force presented UO leadership with a set of demands, including one to change the names of “all of the KKK-related buildings on campus.” In summer 2017, Dunn Hall—then affixed to a wing of the Hamilton Complex and named for a former UO professor who was also the “Grand Cyclops” of the Lane County KKK—was officially renamed Unthank Hall. And in fall 2021, the brand new DeNorval Unthank Jr. Hall, located across Agate Street from Hayward Field, was unveiled.

Read more about DeNorval Unthank Jr.

Lyllye Reynolds-Parker, BA ’91 (sociology)

Lyllye Reynolds-Parker, the namesake of the UO’s Black Cultural Center, is a beloved figure in the Ducks community. Known for her tireless support of students, Reynolds-Parker worked as a student advisor at the UO for 17 years.

Though the campus community has warmly embraced Reynolds-Parker in recent years, this is not reflective of her experience growing up in Lane County. The Black neighborhood where her family lived was demolished to construct the Ferry Street Bridge in 1949, pushing the family to West 11th Avenue, outside of Eugene city limits at the time. Their two-bedroom house was home to 13 people and didn’t have running water. Outside of her tightknit community of people of color, Reynolds-Parker faced prevalent racism, in one instance being told by a school counselor that her opportunities were limited as a Black female.

These experiences inspired Reynolds-Parker to make a difference for Black students and other students of color at the UO, to ensure they feel empowered to pursue the lives they want. She became an adviser in the UO’s Office of Multicultural Academic Success in 1995, after graduating from the UO as a 45-year-old single mother in 1991. She used her own obstacles to overcome as fuel to nurture and inspire others, embracing her students as if they were her own children and improving countless lives.

Reynolds-Parker retired from the UO in 2012, and in 2019, the Lyllye Reynolds-Parker Black Cultural Center officially opened its doors. The center is an academic, cultural, and social home for the UO’s Black students and community—just as Reynolds-Parker was to her students.

Today, she stays connected with the UO community and many of her former students. In 2022, the UO Black Alumni Network recognized Reynolds-Parker with the

Icon Award, part of their inaugural UOBAN Duck Legends Awards.

Polly Irungu, BA ’17 (journalism)

Polly Irungu is an accomplished multimedia journalist, founder of Black Women Photographers, and the first official photo editor for the Office of the Vice President to the Biden-Harris Administration.

Irungu picked up photography in high school, buying her first camera with hard-earned dollars from her first job. After a challenging move from Kansas to the Pacific Northwest after her freshman year of high school, the Nairobi-born alumna began to create a sense of community and passion through photography. She started covering rallies and protests, submitting some of her pieces to CNN iReports, and being recognized for her work.

After high school, Irungu attended the UO’s School of Journalism and Communication, graduating in 2017. Since graduation, she’s gone on to have her work featured in national publications such as The Washington Post, The New York Times, NPR, and more.

In 2020, she began to challenge media outlets like these to increase diversity in the photography field. She founded Black Women Photographers, a global community that promotes the work of Black women and non-binary photographers, connecting them with companies hiring and celebrating their art. The community is now more than 2,100 strong and has provided over $125,000 in grants to Black creatives.

Irungu’s latest endeavor is working as photo editor at The White House in the Office of Vice President Kamala Harris, where she’s had the opportunity to cover a plethora of events and initiatives, even traveling internationally with the vice president.

When speaking with the UOAA back in 2021, Irungu chalked her success to hard work and staying true to herself. She emphasized her focus on highlighting Black joy through her photography.

“A lot of the stories that we see centered around Black folks often feature some kind of Black trauma or Black pain and you don’t often see the moments of joy. Subconsciously I gravitate toward that,” she said.

Read more about Polly Irungu

Kimberly Johnson, BS ’01 (ethnic studies)

Kimberly Johnson is the University of Oregon’s vice provost for undergraduate education and student success and an award-winning author.

Johnson’s novel, This is My America, which has received national acclaim from media outlets like NPR and Buzzfeed, will be produced as an HBO Max series. The book follows Tracy, a 17-year-old Black, Gen-Z high school student in Texas who lives and breathes social justice. Every week, she writes letters to Innocence X asking the criminal justice organization to help her father, who is on death row for a crime he didn’t commit. As she fights to save her father, Tracy's brother is arrested, accused of murdering a White classmate. Curriculum based on the book is being taught in schools nationwide, and the story’s screen adaptation, of which Johnson is an executive producer, will broaden its reach even further.

In writing the novel, Johnson drew on her own experiences being involved in social justice growing up in Eugene. The alumna was president of Eugene’s NAACP Youth Council as a student and has continued her activism for students through her career in advising and higher education. This is evidenced by Johnson’s service through previous roles such as directing UO’s Center for Multicultural Academic Excellence and as alumni advisor for the Oregon chapter of Alpha Kappa Alpha sorority, an historically Black Greek organization.

In addition to overseeing more than 18 offices and programs at the UO through her current senior leadership role, Johnson continues writing. Her novel, Invisible Son, was released in 2023, and The Color of a Lie will be released June 2024. In 2022, the UO Black Alumni Network recognized her with the Innovator Award, part of their inaugural UOBAN Duck Legends Awards.

Read more about Kimberly Johnson

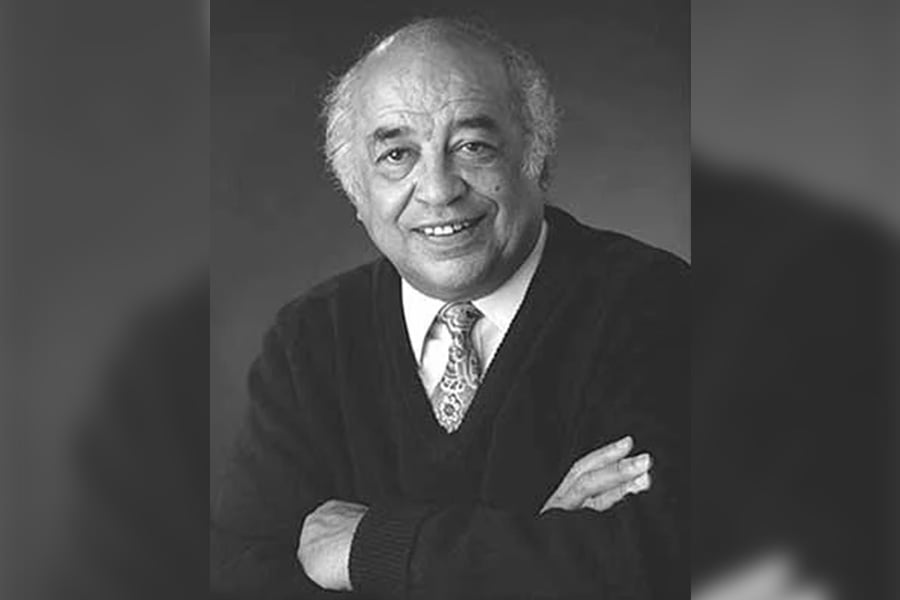

Ed Coleman, PhD ’71 (theatre arts)

Ed Coleman was an educator, musician, and activist, who left a lasting legacy at the UO and throughout Lane County over his five decades in Eugene.

Coleman came to the UO in 1966 to earn his doctoral degree and was subsequently hired as a full-time English instructor at the university. He introduced Black literature to the UO, was instrumental to the launch of the ethnic studies program, and was a fierce advocate for Black students and staff at a predominantly White institution.

Prior to his move to Eugene, Coleman became an accomplished jazz performer. While stationed in Spokane as part of the Air Force reserves, he began playing shows in the area. His talents were well-known—he performed with Ella Fitzgerald and even toured with Peter, Paul and Mary. When touring in the 1960s and 1970s, Coleman faced racism and discrimination, often disallowed from White-only hotels, and was forced to sleep in a vehicle.

His musical talent was first born at age six, when Coleman began playing the violin. He and his family were living in Arkansas under Jim Crow laws. During World War II, the family moved to Alameda, California, where they lived in a racially segregated housing project. Coleman attended a predominantly White high school in the Bay Area, where he expanded his musical education. At the UO, he regularly incorporated music in the classroom.

In addition to his musical and academic endeavors, Coleman gave countless hours to students and the university community. He served as an advisor for the Black Student Union and Cultural Center and supporter of the Black Student Task Force, supported a long list of committees at the UO and throughout Lane County, and more.

Coleman retired from the UO in 1998—though he continued teaching for a number of years after that. He passed away in January 2017, leaving an enduring impact on the entire UO campus, but especially for Black students and staff.

Nathan Harris, BA ’14 (English)

Nathan Harris is the New York Times best-selling author of The Sweetness of Water, a novel he started writing while still a student at the UO.

Harris knew he wanted to be a writer from a young age, but it was his time at Oregon when he honed his skillset and started to find his own voice as a writer. From 2013 to 2015, Harris developed The Sweetness of Water while working food delivery for an online service. After graduating from the UO in 2014, he was accepted as a fellow at the Michener Center for Writers at the University of Texas at Austin, where he earned a master of fine arts and finished writing the book.

The novel, which was the summer 2021 selection of Oprah’s Book Club, tells the story of two brothers freed by the Emancipation Proclamation and a Georgia farmer who forged an alliance that alters their lives forever. Running parallel to their story is a forbidden romance between two Confederate soldiers. Harris’s work of historical fiction is set against the backdrop of a violent, prejudiced town and explores complex themes of race and racism, power, love, and homosexuality.

The Sweetness of Water won a number of national awards, including the Ernest J. Gaines Award for Literary Excellence and was included in President Obama’s Summer 2021 Reading List. Harris was also honored as one of five under 35 by the National Book Foundation. In 2022, the UO Black Alumni Network recognized him with the Rising Star Award, part of their inaugural UOBAN Duck Legends Awards.

Read more about Nathan Harris

Read more stories about Black UO alumni and faculty

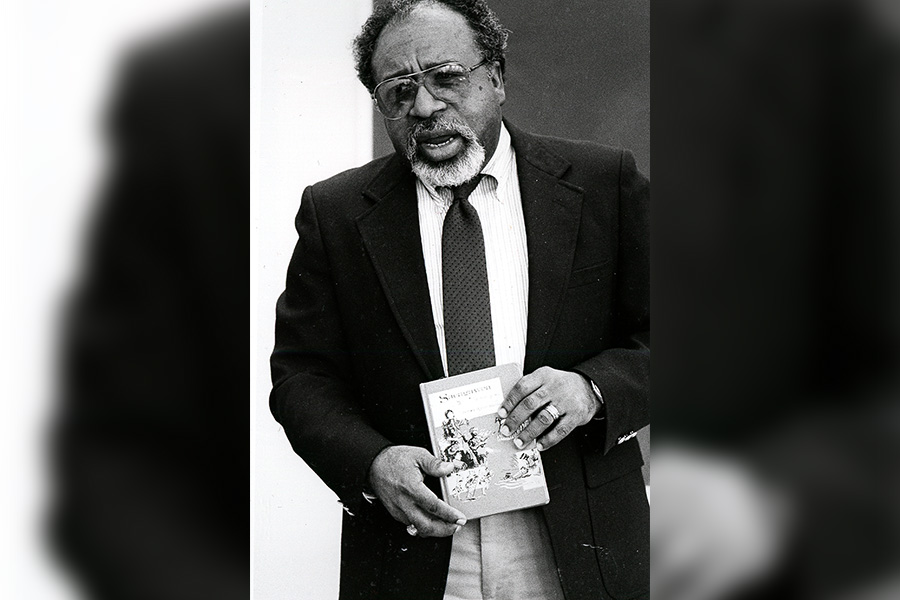

UO History 101: Black Cultural Center

Since 1966, the Black Student Union has been bringing awareness to racial injustice at the UO and advocating for Black students. Two years after its creation, a list of grievances and demands was sent to President Arthur Fleming, and among these included facilities for the Black Student Union. Despite the list of demands, there was little change. Alumnus Herman Brame highlights the history of student life at the UO during the 1960s in the video below.

It was activists and advocates, like Edwin Coleman, Ray Eaglin, BS ’71 (political science), and others who created change on campus through their activism and involvement with the Black Student Union.

In 2015, a march was organized by the Black Student Task Force in support and recognition of the injustices faced by Black students at the University of Missouri and the University of Oregon. A second list of demands was issued, almost fifty years from the original. Among the twelve demands was to fund and support the opening of a Black Cultural Center on campus.

On October 12, 2018, the groundbreaking ceremony for the Lyllye Reynolds-Parker Black Cultural Center took place on East 15th Avenue between Moss and Villard streets. A year later, the center officially opened, serving as an academic, cultural, and social home for the university’s Black students and the community.

Editor’s note: This blurb was adapted from UO History 101: Black Cultural Center written by former UOAA student associate Peyton Hall.

Read more about the Black Cultural Center

UO Black Alumni Network

The UO Black Alumni Network (UOBAN) connects Black alumni and provides support to current Black UO students.

Since its establishment as a UOAA affinity chapter in 2016, UOBAN has been building upon its three pillars of mentorship, relationship, and scholarship. The group is building a strong network for Black Ducks, fostering a sense of community through engaging events such as an annual tailgate and triannual reunion in Eugene and a Black Wealth Series hosted in the Portland area. Upcoming events include a Black History Month Happy Hour at Mermosa PDX on February 29 and BIPOC Flock at the Blazers on March 6, a partnership with several other BIPOC alumni networks.

Last year, UOBAN and the UO Alumni Association launched the UO Black Alumni Network Student Support Fund, which supports the recruitment, retention, and graduation of Black students at the UO. The goal of the fund is to establish an endowment to provide financial assistance to first year, transfer, and graduate students, to bridge historic wealth gaps by reducing student debt and promote academic success. To learn more and donate, click here.