Why War in Korea?

The Korean war finds most Americans bewildered. Why, just five short years after victory over the Axis powers, are American boys fighting and dying in this small, insignificant and little-known country in the Far East? The answer, of course, does not so much lie in Korean politics as it does in the American-Russian rivalry that has grown first into the cold war and now into the first installment of a hot war. But why did the conflict begin in Korea?

Both Czarist and Communist Russia have had intense interest in this part of the world. Blocked effectively in Western Europe, the USSR turned its active attention to the Orient. The billion people of Asia, underprivileged and oppressed, offered an excellent field for the spread and acceptance of the doctrines of Communism. The inclusion of South Korea in the Soviet system would give Communism an unbroken stretch on the east coast of Asia stretching from the northernmost tip of Siberia in the Arctic circle to the southern border of China.

Failure to include South Korea in the Communist orbit would mean that a wedge that could be made into a bridgehead would be left threatening, in a military sense, the position of Siberia, Manchuria, and China.

Korea is a peninsula thrusting from the Asiatic mainland southeast by south into that part of the Pacific ocean known as the Sea of Japan. In area it is roughly the size of the state of Utah. Its population has recently been estimated as approaching 30 million, two-thirds of the people living south of the 38th parallel.

The peninsula is about six hundred miles long and averages about 125 miles in width. In a military sense it has a two-edged strategic value. The southern tip is separated from Japan by a strait only slightly more than a hundred miles in width. Occupation of South Korea by a hostile power endangers the military establishment in Japan. But Korea has also, historically, been the highroad of invasion from Japan to China. It also outflanks Manchuria and Siberia. So, the occupation of South Korea by a power hostile to these countries endangers them.

Over the many centuries of its existence, Korea was loosely held in the Chinese empire as a vassal state. When Japan, in mid-nineteenth century, decided to enter the modern world system of power politics, Korea was marked down for detachment from the Chinese. The struggle between China and Japan for Korea finally resulted in the Sino-Japanese war of 1894-95. Japan won this war but was unable to go ahead with its Korean plans, for Russia stepped into the vacuum created by China's loss.

Russia and Japan, after a ten-year political contest over Korea, finally waged war in 1904-05. Again Japan won. In 1910, Japan was finally able to fulfill its ambition and Korea was formally annexed as a colony. For the next 35 years, Korea was under Japanese colonial administration. However, in Korea the desire for independence never died. During this period there were many Korean underground parties, some of the strongest being Communist-led.

During World War II, as part of the plan to break up the Japanese empire, certain international undertakings were entered into by the United Nations concerning Korea. At Cairo, in November 1943. it was agreed among the United States, the United Kingdom and China that "in due course of time, Korea shall become free and independent." At Yalta, in early 1945, the decision was made for the entrance of Russia into the war against Japan. At Potsdam, in July, 1945, it was agreed that the zone of military operations for the Russians in their fight against the Japanese would be north of the 38th parallel; the zone for American military operations in Korea would be south of this line. When Russia entered the war, in the few days before the Japanese surrender, her troops entered North Korea. After the Japanese surrender, she quickly occupied the remaining portion of her zone.

The Japanese surrender caught the United States unprepared in its Korean policy. It was nearly a month before the United States could send troops to South Korea and then plans were formed only for the acceptance of the surrender of the large Japanese army that was in Korea. The American army, under General Hodges, was met by an involved political situation. Several days before the American forces landed, a convention of Korean parties was held and out of this convention came the establishment of a People's Republic. The United States refused to recognize this government as the free and independent government of Korea.

It was argued that the best organized of the Korean parties that had participated in the establishment of the People's Republic had been the Communist parties, that this had been unfair to the unorganized non- Communist parties. Our position was that in order to see that the government for a free independent Korea represented the true will of the Korean population, the establishment of the government should wait until all parties had had time to organize. In fact, the People's Republic was Communist-dominated. But the reaction of the majority of Koreans, both Communist and non-Communist, was bitterly anti-American. The United States had been placed in the uncomfortable role of having kept the Koreans from becoming independent. Our position was made worse by our lack of trained American military government personnel to take over the administration of the country, and our subsequent use of the old Japanese officials. It took the United States several years to overcome these initial disadvantages.

In the north, the Russians were in no such predicament, for it afforded them no embarrassment to recognize the Communist dominated People's Republic.

This difference of opinion between the United States and Russia was placed on the agenda of the meeting of the Council of Foreign Ministers that met in Moscow in December. 1945. An agreement for the settlement of the Korean problem was worked out when the council agreed that a four-powered trusteeship would be set up for the governing of Korea. It was further agreed that this trusteeship would last for a period not longer than five years, and that during the period of trusteeship the Koreans would go ahead with establishment of an independent government by democratic processes.

The reaction of the Koreans, with one notable exception, to this plan was immediate and violent. All of the non-Communist parties bitterly protested what they felt was another postponement of their independence. The notable exception was the group of Korean Communist parties who did not criticize the agreement to which Russia was a party.

In accordance with the Moscow agreement, early in 1946 the American and Russian military commanders in Korea met to establish the rules by which the Koreans could start working on the establishment of their own independent government. These conferences almost at once became deadlocked over the question of what Korean political groups would be allowed to participate in the establishment of the government. The Russians insisted that only those parties that had not protested the trusteeship should be allowed participation! Of course, this excluded practically every Korean who was not bound by the discipline of the Communist party. The American position was that all parties, including the Communist party, should participate if the government were to be democratic.

The discussions were soon abandoned and the 38th parallel then became a line marking off the political division of the country. After fruitless attempts to settle the question by bi-lateral action, the United States finally referred the question to the United Nations General Assembly.

In 1948 the General Assembly decided to sponsor a democratic election in Korea for choosing representatives to establish an independent Korean government. Although the decisions of the General Assembly are not subject to veto, the Russians boycotted the General Assembly action. The General Assembly decided to go ahead and to hold the elections wherever possible in Korea. A commission was sent to Korea to supervise the elections. This commission was denied entrance to the territory north of the 38th parallel. The elections were held in May 1948, in South Korea, the United Nations' commission reporting that they had been held in a democratic fashion.

The representatives chosen in the election met in July, formed a constitution which set up the framework of the Korean government. In the legislature that was established, seats were left vacant for the North Koreans whenever they wished to enter the government. Thus by August a Korean government was established, sponsored by the United Nations, which laid claim to being the legitimate government for all Korea. The Russians in the north quickly countered this by the establishment of a Peoples Republic which, too, claimed to be the government for all Korea. Thus the Koreans were drawn into the large issue of American-Russian rivalry. Civil war was inevitable.

Russian and American military forces were soon withdrawn from the country. However, both sides left behind military missions to train the armies of the two governments. For whatever reasons that may be ascertained later, the United States failed to equip the South Koreans with the two major necessities of modern warfare: armor and an effective airforce. From 1948 to the outbreak of the war, the United Nations' commission continued its work, without success, trying to bring the two governments together. Finally, in the last of June 1950. the civil war broke out when the North Korean forces invaded south of the 38th parallel. It is difficult to conceive, knowing the discipline that is exerted within the Communist parties, that the invasion was not undertaken without the specific decision having been made by the USSR.

That aggression posed for the United States as the leader of the world's anti-Communist countries the grave question of what to do about it if the dreary scenes of the 1930s were not to be repeated. We chose to sustain South Korea by Military force, acting in the name of the United Nations. The meaning, then, of Americans fighting in Korea is to sustain the principle of collective security, of collective action against military aggression.

To prevent other Koreas from happening, in a world that could not long stand an atomic war between the United States and Russia poses a larger problem.

The first step would seem to be the clear establishment of the rules of humanity by which we desire to live, the organization of all countries who wish to abide by these rules so that there may be provided a police force to enforce them.

The second and equally important step is a reexamination of the nature of the struggle between the United States and Russia. We have been too much inclined, it would seem, to think of the struggle against Communism in terms only of how much physical force it will take to contain it. Perhaps it would take less physical force if we were to shift to the question of what ideas are necessary to contain it. Much of the Communist success has taken place in areas where the mass of people are underprivileged and are grasping for freedom. It is time that we remembered and put into practice in our foreign policy the proposition that democracy stands for more freedom than the police state can ever grant.

In this contest for men's minds, they must be given the choice between our kind of freedom, and Communism—not between Communism and their old oppression. Can there be any question that if they really were given that choice that there would be the danger of defeat for our ideology?

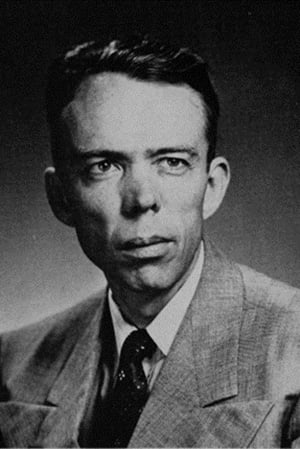

THE AUTHOR, Dr. Paul S. Dull visited Japan, Korea and Manchuria in 1938. He was with the Marine corps as Japanese language officer at Pearl Harbor. Later as a civilian he was acting chief of Japanese intelligence section and editor of Japanese propaganda division, Office of War Information, psychological warfare branch. He received his doctorate from the University of Washington, then was granted a post-doctorate Rockefeller fellowship to Harvard in Far Eastern studies. He has been at the University of Oregon since 1946. Associate professor of political science and history, he is coordinator of the Far Eastern studies curriculum, which encompasses the fields of language and literature, political science, history, anthropology, economics, art, and religion—as related to the Far East.

- October 1950 from Old Oregon