Blazing a Path to Wilderness

Over the span of five years beginning in 1984, Congress enacted laws preserving more than seven million acres of wild national forest lands as wilderness, including 854,000 acres in Oregon. A federal lawsuit in Oregon filed by Neil Kagan, JD ’81, spurred this legislation.

The evidence that the lawsuit had this impact is in the legislative history, which Kagan documents in a new article titled Blazing a Path to Wilderness: A Case Study of Impact Litigation through the Lens of Legislative History, 11 Mich. J. Envtl. & Admin. Law 87 (2021).

The legislation finalized a process that began in the 1970s, when the US Forest Service began evaluating 62 million acres of national forest lands in 38 states to decide which of them it should recommend for addition to the National Wilderness Preservation System.

“In the late 1970s, an impasse had developed nationally over the allocation of roadless areas in national forests, whether to wilderness or non-wilderness uses,” says Kagan. “The industry wanted as much forest land as possible to be available for timber harvesting. The environmentalists wanted as much as possible preserved as wilderness.”

In 1979, the Forest Service recommended that Congress preserve only a small fraction of these forests as wilderness. In Oregon, for instance, they recommended only 368,120 of almost three million acres of wild forests for preservation.

Kagan notes that the agency’s recommendation did not include the 21,000-acre Boulder Creek area, located in the Umpqua National Forest, east of Roseburg. It was there that Kagan and his late wife, Betty Reed, JD ’81, frequently hiked.

“The pines shoot straight up 100 feet or more. Some are so enormous that when Betty and I stood on opposite sides of a tree and reached our arms around the trunk, we couldn’t touch each other’s fingers,” recalls Kagan.

Through 1983, Congress was mostly deadlocked over the Forest Service’s recommendations regarding the disposition of wild areas in national forests. Meanwhile, the wild forests in Oregon that had not been recommended for preservation were beginning to be actively logged and subdivided by roads, destroying their wilderness character.

In December 1983, to stop this destruction, the Oregon Natural Resources Council (ONRC, now known as Oregon Wild) asked Kagan to challenge the sufficiency of the Forest Service’s evaluation of the wild forests in federal trial court.

“Because of the lawsuit’s impact, Congress was forced to act. Because Congress acted, more than seven million acres of wild forests remain wild.”

“At the time, I was a solo practitioner with only a few clients,” says Kagan. “Betty and I were living from paycheck to paycheck—her paycheck as an assistant district attorney. Nevertheless, Betty readily agreed I should represent ONRC pro bono, because the group could not afford to pay a lawyer. She knew that meant I would be passing up the opportunity to work for clients who would pay me.”

The Forest Service was aware that a federal appeals court had previously judged the evaluation of wild forests deficient in a case concerning wild areas in California’s national forests. In January 1984, anticipating the same outcome from the Oregon lawsuit, the Forest Service froze the exploitation of all wild forests in Oregon released from wilderness consideration during the pendency of the lawsuit.

“The freeze on logging across more than two million acres in Oregon triggered by the lawsuit pressured Oregon’s senior Senator, Mark Hatfield, to push legislators opposed to expansive wilderness legislation to compromise,” says Kagan.

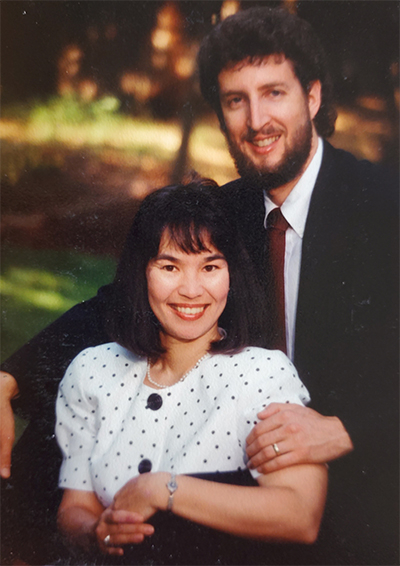

Neil met his late-wife Betty the first day of law school on August 24, 1978. “That day is the luckiest day of my life because it's the day I met the love of my life.” Photo Credit Neil Kagan

The compromise opened the way to 18 wilderness laws in 1984 and five more from 1985 through 1989. These laws preserve 7.335 million acres in national forests in 23 states as wilderness, nearly twice the acreage the Forest Service had recommended for wilderness preservation in those states collectively.

“Because of Betty’s financial and moral support, the Oregon lawsuit became a reality,” says Kagan. “Because of the lawsuit’s impact, Congress was forced to act. Because Congress acted, more than seven million acres of wild forests remain wild.”

In Oregon, Congress both added new components and expanded existing components of the National Wilderness Preservation System. It added 23 new wilderness areas totaling 681,100 acres. One of them was the Boulder Creek Wilderness. Congress expanded seven existing wilderness areas by a total of 172,900 acres. Since 1984, Congress has preserved an additional 114,172 acres in six areas in Oregon’s national forests.

The article Blazing a Path to Wilderness complements a story that describes the emergency litigation Kagan earlier prosecuted that stopped the destruction of a wild forest of 113,000 acres in Southern Oregon, which set the stage for the statewide lawsuit. That story is told in Wilderness, Luck & Love: A Memoir and a Tribute, 7 Mich. J. Envtl. & Admin. Law 315 (2018).

-By UO Alumni Association Communication