Oiselle founder Sally Bergesen, BA ’92 (English), almost didn’t become a Duck.

In fact, she almost didn’t become a college student at all.

“I grew up in Berkeley, California, in the 70s and basically, at that time, parents saw school as indoctrination and encouraged children to just be themselves and not even worry about it,” said Bergesen. “So, needless to say, my grades in high school were not great.”

Bergesen’s father encouraged her to rebel against the rebellion though, and check out universities on the East Coast. However, a trip to Eugene ended any thoughts of moving to the Northeast.

“We went up and visited [the UO campus] in person,” Bergesen said. “It was when I was still deciding, and it was a beautiful day in Eugene, and, you know, Eugene on a beautiful day is a beautiful place. I remember falling in love with the campus, and the buildings, and the walkways. I rented a bike, and Eugene is such a great bicycle town, it was just so easy to ride around and see the sights. It was probably my first time going to the Pacific Northwest, and it had a different feel but was very natural and had beautiful scenery.”

Bergesen dove into her studies at the UO, and discovered a love of literature and the arts.

“I was an English major so I loved reading books, and I loved writing,” she said. “I got plugged into those classes where I had interesting professors and interesting books. I read 1984 my freshman year at Oregon, and Brave New World, a lot of just seminal books. I took art history, which was kind of a wild card class. I loved that class and I would say in some ways that led to my eyes being open to design.”

But, like many Ducks, Bergesen fell in love with running while in Eugene—after first falling in love with now-husband Alec Duxbury, a student at the University of Washington she met while the pair were studying abroad in France. Duxbury was a cyclist who lived a healthy life, while Bergesen… didn’t. “He was living this athlete lifestyle and I was kind of like, ‘Huh, that's interesting,’ as I'm like smoking my cigarette in France,” Bergesen recalled.

After returning to the UO, Bergesen—who ran track her senior year of high school in California—elected to get back into running. When you live near Pre’s Trail, the Rexius Trail, the Ruth Bascom Riverbank Path System, Dorris Ranch, the Fern Ridge Trail, Hendricks Park, and the Ridgeline Trail, the options are as plentiful as the shoe choices at RunHub Northwest and the Eugene Running Company. When Bergesen wasn’t reading Orwell and Huxley she was running a loop that included Pre’s Rock, Hendricks Park, and the Amazon Parkway, and after graduating from the UO she simply didn’t stop.

Bergesen worked as a paralegal for six years, then followed her creative passion and joined a design agency in Seattle where, among other things, she coined the term “Plan B” for the morning-after contraceptive.

All the while she continued to run, calling it “a new tool in my toolbox in terms of mental health and just helping me figure out what I wanted to do with my life.” She raced competitively throughout the Northwest during her 20s, pausing to take a break only when she had children—her first in 1999 and her second in 2003. When she went to get back into running though, she found a problem—her options for running shorts were less than ideal.

“I just felt like my love of running was on this really high level, but my experience with the product was really at a low level,” Bergesen said. ”That was kind of my lightbulb moment. At the time I wasn't like, ‘I’m going to create a running company and a brand and a community,’ you know all these big, big things. I really just wanted shorts that fit better, felt better, looked better. And that was kind of like that first idea that I thought I might be able to tackle.”

After the idea came the name, and Bergesen drew on her design agency skills—and her study abroad trip to France—and came up with Oiselle (pronounced wa-ZELL) for her fledgling company.

Sally Bergesen (front row, far left) with members of the Oiselle Volée.

“I always loved naming, playing with words,” she said. “I knew as a namer that the sweet spot for a brand name is a name that is very unique and is memorable, and I wasn’t shy about choosing a word that Americans might struggle with a little bit because I think, you know, that’s fine. People will figure it out. Also, if you know how to pronounce the brand name you’re kind of like in the club a little bit. It kind of drew all those things together, my expertise in naming as well as my love of the French language. The word itself means ‘bird’ in French, but it’s kind of an antiquated word. It actually means 'female bird.'”

With an idea and a name in place, it was time to build the brand and get the product on shelves nationwide. Bergesen compares building Oiselle to distance running—“It’s about the training, and the daily effort, and knowing that big leaps forward don’t happen overnight. They happen by focusing on the details and taking care with every step,” she said. There were stops and starts. There were moments where Bergesen came close to losing everything.

But, slowly but surely, Bergesen—who started off just with a narrow focus on shorts—ended up doing so much more.

The Oiselle website includes information about the charitable program Bras for Girls; a section on how the female body changes during puberty; warning signs about problematic coaches; a training glossary; training plans; running tips; a library of books, newsletters, and podcasts; runner meet-ups; a Black Voters Matter relay; Volée (to ‘take flight,’ or ‘soar’), Oiselle’s global network of runners who can train, run, and attend fun events together; an annual camp; blog posts; information about famous female athletes from throughout history; and more.

You name it, they have it—and “it” includes shoes, bras, T-shirts, and, yes, shorts. Bergesen couldn’t find any she liked in the store, so she went and designed them herself and sold them to the public.

Kara Goucher, Lauren Fleshman, and Sally Bergesen.

For any apparel company visibility is key, and for an athletics apparel company in particular that means getting your logo on elite athletes. Enter Haute Volée, Oiselle’s roster of more than 40 Olympic and Paralympic hopefuls, which includes distance running legend and two-time Olympian Kara Goucher, two-time USA 5k champion Lauren Fleshman, top steeplechaser Mel Lawrence, Team USA world indoor championships and world relay team member Kendra Chambers, 4x800m collegiate record holder Angel Piccirillo, US Paralympic Team member Jenna Fesemyer, two-time Olympic race walker Maria Michta-Coffey, and more. But, for Bergesen, the process of selecting who will represent Oiselle involves evaluating them as people just as much as evaluating them as athletes.

“We really do look for athletes who are interested in telling that fuller story,” said Bergesen. “Some athletes would prefer to just have their performances be what speaks for who they are, and sometimes that's understandable considering how much it takes to train and be at that high level.

“But we have found that for us, what’s a better fit for our brand are athletes who are interested in doing well athletically and care a lot about advocating for and changing sports as a whole, especially as it comes to women’s rights, the rights of people who have been marginalized, and to now to speaking about trans inclusion in sports. Speaking out on those issues actually requires a lot of conviction and a lot of courage, so the selection process has something to do with also how athletes feel about being a part of that journey as well.”

Goucher and Fleshman now serve in more of an advisory and coaching role—they provided Oiselle’s free half marathon and marathon training plans respectively, plans that include running glossaries, tips for how to mentally approach races, and their favorite pieces of Oiselle clothing. Joining them as a third lead athlete advisor in 2020 was Alison Mariella Désir, a well-known sports activist and co-founder of Harlem Run and the Running Industry Diversity Coalition.

But there will still be plenty of Oiselle representation at the US Olympic Team Trials – Track and Field when they get underway at Hayward Field on June 18. As of June 1, Oiselle’s qualified athletes were:

- Dani Aragon, 1,500m

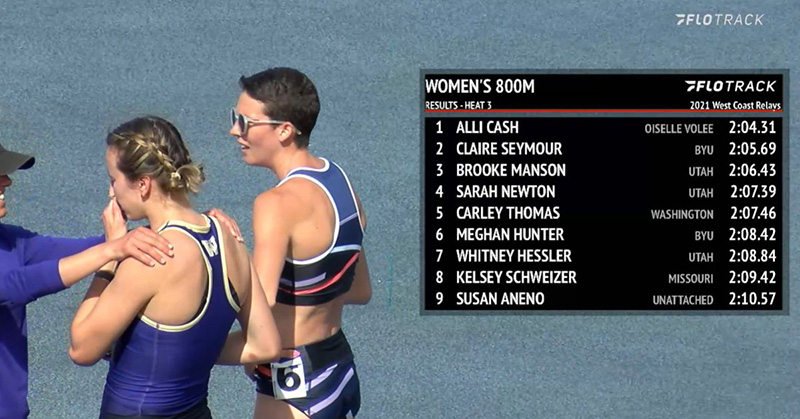

- Alli Cash, BS ’18 (human physiology), 1,500m

- Kendra Chambers, 800m

- Megan Clark, pole vault

- Riley Cooks, heptathlon

- Sadi Henderson, 800m

- Mel Lawrence, 3k steeplechase

- Rebecca Mehra, 800m

- Maria Michta-Coffey, 20k race walk (will be held in Springfield)

- Malaina Payton, long jump

- Sarah Pease, 10,000m

- Angel Piccirillo, 1,500m

- Madeline Strandemo, 3k steeplechase

In addition to those 13, pushrim racer Jenna Fesemyer will be competing at the Paralympic Trials in Minneapolis, Minnesota, from June 17–20.

“It’s always such an honor to just play a role in an athlete’s journey who has made it to that level,” said Bergesen. “One of our mottos is, ‘The best way to get fans is to be a fan.’ So we like to just show up and be fans.”

But getting involved with sponsoring professional athletes means wading into the murky waters of, well, professional athletics. When it comes to the dollars and cents side of things, track and field isn’t exactly Major League Baseball or the National Football League.

Former UO javelin thrower and two-time Olympian Cyrus Hostetler, BS ’10 (art) estimates he never earned more than $3,000 in a year after expenses, and was on food stamps while training for the 2016 Olympic Games in Rio. While Tom Brady earned a $1 million bonus for winning the Super Bowl with the Tampa Bay Buccaneers earlier this year, a Team USA member who wins a gold medal in Tokyo in July will receive less than $40,000—despite a global audience of more than three billion people tuning in to watch the Olympics. The Summer Olympics is the most popular sporting event in the world—marginally more popular than the FIFA men’s World Cup—but more than half of all American track and field athletes ranked among the top 10 in the USA in their disciplines earn less than $15,000 per year.

For track and field athletes, then, their apparel sponsorships are tremendously important—they’re literally the difference between living comfortably and living on food stamps. For the clothing brands they’re just as important, as the sponsored athletes become faster, higher, stronger billboards in front of a global audience.

Only, the International Olympic Committee relies on the income it receives from its own sponsors and television partners, and doesn’t want to do anything to rock the boat. Until it was amended following the 2016 Olympics, the IOC’s Rule 40 prohibited athletes from using their own name and likeness or mentioning non-approved sponsors during a blackout period that covered a period that begins during the leadup to an Olympic Games and ends after the conclusion of the Games. For example, had Goucher made Team USA as an Olympian and then won the gold medal in Rio, she would not have been allowed to post a tweet to her 127,000 followers thanking Oiselle for their support, nor would Oiselle have been allowed to make a post on Instagram to their 97,000 followers congratulating Goucher. In fact, Oiselle was not even allowed to acknowledge the Olympics were even occurring—even retweeting NBC Sports or wishing Team USA “good luck” would have landed Bergesen and her company in hot water.

Oiselle runner and UO alumna Alli Cash, BS '18 (in sunglasses) after a meet in California in May. Cash will attempt to make Team USA squad for the Tokyo Olympics in the 1,500m during the Olympic Trials at Hayward Field from June 18–27. Photo from FloTrack.

Bergesen has been one of the voices protesting Rule 40 over the last eight years, and it has since been loosened somewhat—a company can now acknowledge an athlete as long as it’s done as part of an ongoing campaign and they’re not acknowledging the athlete more often than they would in a non-Olympic year; an athlete is allowed to thank their sponsor up to seven times. There are no restrictions on how frequently they can thank an official sponsor, though. Should UO alumna and Oiselle 1,500-meter runner Alli Cash make the Team USA roster this summer, she can thank Oiselle seven times, and thank French IT company Atos as often as she likes.

The off-track battle this year is shaping up to be fought over not Rule 40, but Rule 50. Sports and politics are intertwined—beyond just the back room dealings that can go on when Olympic host cities are being decided, images showing athletes standing up for the rights of others have become iconic throughout the years. Think Tommie Smith and John Carlos raising their fists during the playing of “The Star-Spangled Banner” after Smith won the 200-meters at the 1968 Olympics; or Cathy Freeman, a member of the Kuku Yalanji Aboriginal people in Australia, carrying the Aboriginal flag on her victory lap after winning the 400-meter title at the 2000 Olympics.

But, in a year after George Floyd’s murder sparked an outcry around the world about how Black people are routinely treated—or, to be more accurate, mistreated—the IOC is reiterating that athletes cannot stage any form of protest or demonstration on the field of play, in the Olympic village, and during ceremonies (including medal ceremonies and the opening and closing ceremonies).

By their own definition, a protest could be something as simple as a hand gesture. As iconic as Smith and Carlos’ raised fists are, the IOC president ordered the pair to be suspended from the US Olympic team as a result of their gesture. Australian runner Peter Norman, the silver medalist in the race, wore a Human Rights badge in support of Smith and Carlos; the Australian Olympic Committee snubbed him for the 1972 Olympics when he was ranked fifth in the world, and he was not asked to appear alongside fellow Australian medal winners during a VIP lap of honor at the 2000 Sydney Olympics.

“There's just been so many restraints on athletes, and I think there’s a lot of frustration among activists in general about some of the hypocrisy of the governing bodies and the IOC in general,” said Bergesen. “As we all know, athletes who have protested in the past have been completely destroyed. Tommie Smith and John Carlos from the 1968 Mexico City Olympics are now being inducted into the Hall of Fame by the USATF, the same organization that basically told them they no longer could participate in the sport.

“I think you just see new versions of that in the current era, around Black Lives Matter or around the rights of athletes to make a statement on the podium to speak up against inequity…. That's why it’s important to continue to call it out and to highlight it and to make sure that the broader public is aware and can hold the IOC and the USOPC and the USATF and all the governing bodies accountable, because it’s not like the IOC can say it’s not a political entity with a straight face.”

When the Tokyo Olympics finally get underway in July, Bergesen won’t be there. With the current COVID-19 travel restrictions in place, she’ll be back in Seattle watching from her home. But, knowing that the best way to get fans is to be a fan, she’ll be wearing a pair of comfortable Oiselle shorts while she watches the athletes go for gold.

“The Olympics will be exciting if they all come together and they happen,” said Bergesen. “I’m really excited to cheer for absolutely every athlete that has made that journey. Whether they are a Oiselle athlete or not, it will be very exciting.”

- by Damian Foley, UO Communications. All photos courtesy Sally Bergesen and Oiselle unless otherwise noted.