In her 20 years as a career counselor at the University of Oregon, Clarice Wilsey helped many students discover their ‘callings.’ But after rediscovering a trunk left behind in her parents’ attic after their passing, she realized that she had found another one of her own.

Clarice’s father, Dr. David Wilsey, had always told her that the trunk—and the contents within—were strictly off limits. Revered by the public as an upstanding doctor and family-man, those closest to him knew a different side of him, one withdrawn, authoritarian, and, at times, frightening. He was a man of numbers, a man of science, and a man of God, but at home he was haunted, making it a point to never talk about his past.

Except, of course, on the rare occasion when someone on the television would imply that the events of World War II and the Holocaust were a hoax.

“I was there. I saw it,” he’d then stand and shout, to the bewilderment of children.

Opening that trunk, that metaphorical Pandora’s box, Clarice finally found out why.

After having served as an anesthetist—a brilliant one, as demonstrated by his numerous accolades and the testimonies of peers and patients alike—during World War II, Dr. Wilsey was one of 27 physicians tasked with liberating Dachau (pronounced Daw-cow) and its 40,000 survivors—the first, and perhaps one of the most brutal of Hitler’s concentration camps. Originally established to hold political prisoners, its walls would eventually see the deaths of over 32,000 people and haunt the lives of thousands more.

Clarice’s father was one such person, as portrayed in the more than 300 letters Clarice’s mother, Emily Wilsey, had saved. Serving as first-hand accounts, the letters and photographs depict the horrors that warped one man’s optimism, lovingness, and morality by the end of his service—ultimately impacting his family.

One such letter implored Clarice’s mother to “tell the world what happened … so that millions will know what Dachau is—and never forget the name.”

When Clarice read those words, she felt a new calling. She would make it her mission to break the bonds of intergenerational trauma and counter the silence surrounding the Holocaust and the effects of war-related PTSD. In fact, she would write a whole book about it.

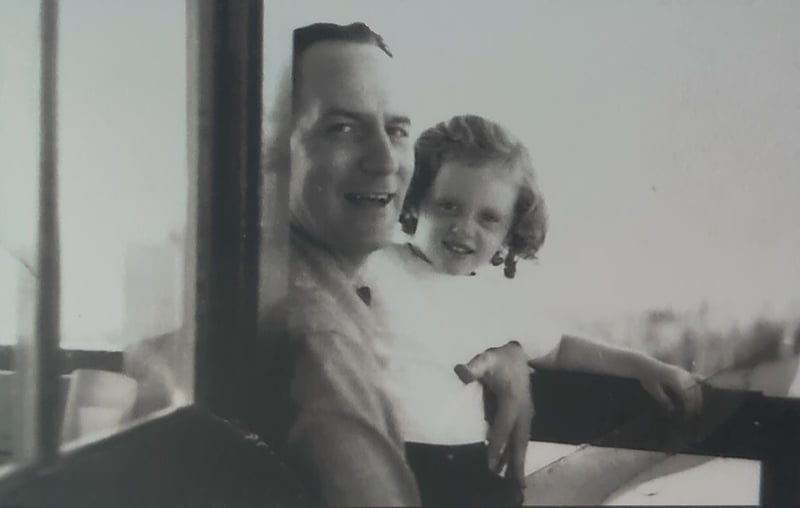

Clarice Wilsey and her father, in an image from the dust jacket of Wilsey's book Letters from Dachau: A father’s witness of war, a daughter’s dream of peace.

Coincidences and Connections on Campus and Beyond

The book itself, however, took more than ten years to write and began, in a sense, as just a feeling that germinated long before she even opened the trunk.

In 2006, Clarice attended a conference as a representative for the UO and decided to go sightseeing at the Smithsonian Institution in D.C.

When the driver announced a stop at the U.S. Holocaust Museum, she made a decision that would forever change her life—she got off at that stop instead.

Inside the Holocaust Museum, a stranger randomly let her go ahead of the rest of the line, a moment which led to witnessing her father walking across the screen of an exhibit featuring a newsreel from Dachau.

But Clarice does not believe it was a coincidence.

“How amazing is it that I would be at the elevator, in that long line … we go up to the fourth floor. The door is open, and at that exact second, my dad is walking across. To me, that is God,” she said about the experience that would later act as a catalyst for her writing.

Clarice retired from the UO in 2019 to work on her publication and Letters from Dachau: A father’s witness of war, a daughter’s dream of peace was published in April of 2020—75 years after the Dachau’s liberation. The 201-page memoir is painstakingly researched, telling the story not just of her father during the war, but how the war influenced their family in the years that followed.

But writing a book proved to be no easy feat for Clarice. A self-proclaimed extrovert, Clarice said “she never could have sat in (her) house alone, writing a book.”

So, she enlisted the help of Bob Welch, retired professor of journalism at the UO and former columnist at The Register Guard, to act as co-author. It was he who convinced Clarice to include her personal story while also detailing her father’s heroics.

“He said to me ‘Clarice, there are a lot of books written about war, the Holocaust, Dachau, what have you,” Clarice recalled, “what there has not been a lot of is books talking about people whose parents’ trauma affected the family, and yet they (the child) still turned out successful.”

Welch was not the only connection made at the UO which propelled the book forward, however.

Another was political science professor Gerald Berk.

After an unnamed UO faculty member told Professor Berk about Clarice’s first seminar at the UO in 2016, he knew he had to contact her—his father had also been a physician and liberator at Dachau, and he wanted to know more. At a café in Springfield, they mulled over photographs together, ultimately discovering one where both of their fathers are standing right next to each other during a retreat in France. Incredibly, they had served in the same unit.

Clarice called the realization of their common denominator “healing,” saying that it made them both teary-eyed.

“I mean, how many times might we have crossed each other on the path to the EMU?” she said.

And indeed, the chances of them ever meeting were slim—Berk was raised in Boston, Massachusetts, and Clarice in Spokane, Washington. Working in different departments left them with no reason to be acquainted, but Berk still credits the UO with bringing them together.

“On another campus, I can imagine this not happening … there is something about the UO and Eugene, a kind of openness here … a sincerity about Oregonians,” he said.

Berk, who currently serves on Lane County’s Jewish Community Relations Council, also commented on the power of their friendship which has since blossomed into a sort of sibling-like bond.

“I think it is really interesting and powerful. My dad was there, and he was Jewish. Clarice’s dad was not Jewish, but they experienced the same thing,” he said, adding “it is remarkable to me as a Jewish person the way that Clarice’s dad was called upon somehow to write these letters (and) how the vision that she has drawn up out of this has deepened my understanding of what it means to be Jewish.”

Both also agree that this ‘coincidental’ meeting has taught them valuable life lessons: that out of strife can come incredible beauty, and that friendship can flourish in the face of adversity.

Clarice Wilsey and Gerald Berk's fathers on retreat together in France after spending five weeks treating survivors at Dachau. Wilsey's father, David, is ninth from the right, with a coat over his arm. Berk's father is next to David, wearing a dark shirt and light pants.

Leaving the UO and Starting a New Chapter

But the coincidences and connections did not stop there and were not limited to the UO—a side-effect, perhaps, of breaking the silence. More and more people contacted Clarice with stories all too similar, hers seemingly becoming that of every child who grew up with a parent affected by war.

And that, essentially, is Clarice’s hope for her publication—to counter Holocaust denial and help others realize that they are not alone, that it is ok to speak up about their experiences.

“When a kid is growing up, they think (the actions of their parents) are their fault,” she said, “they do not have the maturity to understand that it’s not … if even a handful of people (read my book) and think ‘oh this was not my fault’ or ‘oh, now I understand,” then I think there can be some healing.”

Clarice is now a speaker for the Holocaust Center for Humanity in Seattle and the Oregon Jewish Museum and Center for Holocaust Education in Portland, and it should come as no surprise that some of the former career counselor’s favorite people to talk to are students of all ages.

“(Speaking), I realized, would ease the segue (from working as a career counselor), continuing to give me a strong sense of purpose and involve the young people I so enjoyed working with. I like their energy. I like their curiosity. When you look for the best in them, they usually give you their best,” she says in her book.

As a career counselor, Clarice would often pose this question to her students: “when it’s your 80th birthday, how would you like people to remember you?”

Clarice, now 73, has led a lifetime of advocacy that has earned her three major awards, including the UO Anne Leavitt award for making a difference in the lives of students.

She is, undeniably, someone who wears her heart on her sleeve despite having a father who often told her not to, someone whose success was built on helping others succeed, and someone who encourages others to face the demons in their own closets, to heal. Because, to take from her memoir, “when silence prevails, bullies win.”

By becoming the ‘voice of her father’ she is proof that a person can have many ‘callings’ in a single lifetime—if they choose to open the right boxes, that is.

With all these achievements, one might wonder: what’s next for Clarice Wilsey?

Retired Brigadier General Peter Hayes wrote the foreword for “Letters from Dachau” in which he stated that the book “should be considered as a textbook for college and military studies. And should find its way onto bookshelves and smart screens for the general public to better understand the horrors of Dachau and their lingering effects on those who liberated it — and those liberators’ families.”

Perhaps someday it will.

Find Clarice’s book at Amazon and Barnes & Noble, or email Clarice directly for more information.

- by Sage Kiernan-Sherrow, student associate. Photos courtesy Clarice Wilsey.