With the football season underway, it seems proper to focus on two football trailblazers at Oregon; Robert "Bobby" Robinson and Charles Williams, the first two African American athletes to compete at the University of Oregon.

In 1926, the two Portland residents came to Eugene for their academic and athletic pursuits. They were offered full scholarships and recruited by the new Oregon head coach John J. McEwan, an All-American in 1914 at Army.

Both were high school friends and rivals, both were selected First Team All-City their senior years, and both packed the stands at Multnomah Field on gamedays with eager fans fanatically following their athletic performances.

Together, they helped Coach McEwan usher in a new era with the Oregon Webfoots. However, their presence at the university was not fully accepted.

When Robinson and Williams arrived on campus, they were barred from living in the “Whites Only” campus dorms and lived in off-campus apartments during their freshman year.

Historian Herman Brame, BS ’68 (sociology), who wrote the book Forgotten Ducks: The Story of Robinson and Williams, explains that this social situation was not created by the university—but by the state of Oregon.

“The state was founded as a state based on white supremacy,” Brame said in the documentary Racing to Change: Student Life in the 1960s with Herman Brame. “We had the exclusion laws in the constitution which made it illegal for any ‘negro, mulatto to reside in the state of Oregon.’”

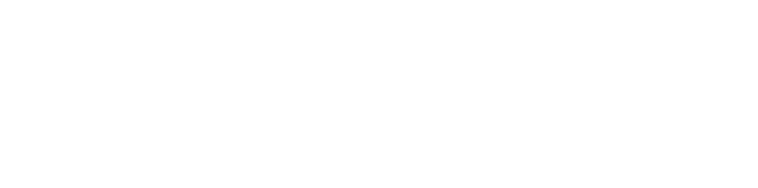

Image of Charles Williams. Photo courtesy of the University of Oregon Special Collections & University Archives

In an era when the Ku Klux Klan had more members in Oregon than any other state west of the Mississippi, Williams and Robinson were resigned to their circumstances.

In an interview with the Register-Guard Emerald Empire (Dec. 1, 1974), Williams recalled his experience. “They [the university officials] were afraid—that’s what I thought,” Williams said, “It was a Ku Klux town and they thought there might be trouble from the townspeople. We accepted that.”

However, their White teammates became unexpected allies in their struggle.

The other football players signed a petition and submitted it to the school under protest, demanding that Williams and Robinson be allowed to live on campus in the dormitories with them.

By their sophomore year, the university relented, and they were permitted to reside in Friendly Hall. However, because of continued segregation policies, Williams and Robinson were separated from their team and only permitted to enter the building through their own designated entrance.

“I suppose to the university it wasn’t quite the same as putting us right in the dorm, but it was to everyone else,” Williams told the Register Guard in 1974. “We had the use of the dorm. We were right with the fellows we knew. We visited back and forth and did everything we wanted.”

An era of change

Even with the duo in key positions, success on the field was not immediate. A string of loses prior to Coach McEwan’s arrival meant Oregon was not drawing quality talent to the program the way they once had.

Coach McEwan did something revolutionary. Going beyond merely having Black athletes on the roster, he chose to place Robinson in the quarterback position.

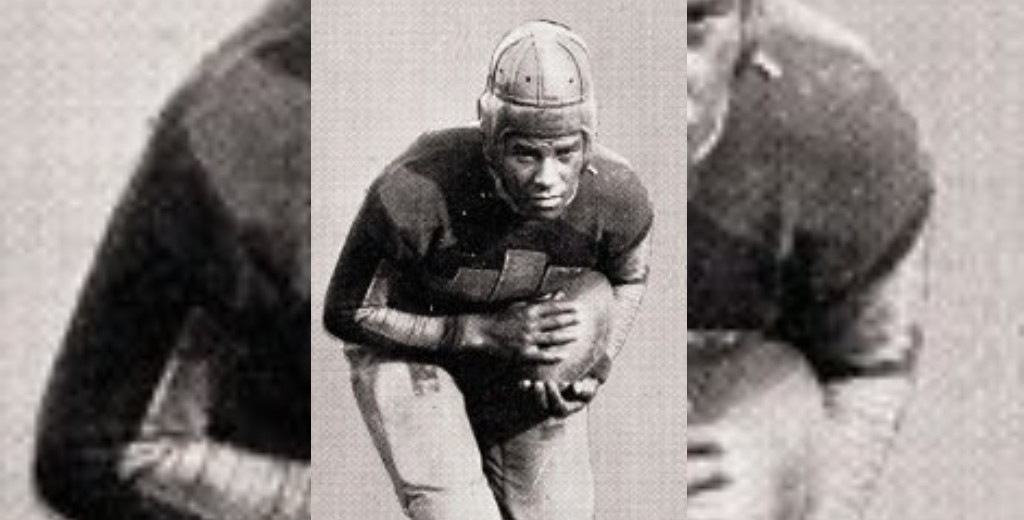

In fact, Williams and Robinson were used all over the field to maximize their talents. Robinson played quarterback, halfback, receiver, defensive back, and returned punts and kickoffs. He was also a pole-vaulter on the track team. Williams played fullback, halfback, and defensive back.

The 1927 season started off with the Portland duo on the field with the varsity team for the first time. Wins over Linfield and Pacific had the Ducks thinking that the tide of recent losing had turned. However, a 0-0 tie to Idaho followed by four straight losses to end the season dashed those hopes. Despite the 2-4-1 season, Robinson and Williams shined in their roles.

Image of Robert "Bobby" Robinson. Photo courtesy of the University of Oregon Special Collections & University Archives

The next football season in 1928 brought a remarkable turnaround and return to national attention for Oregon. They were led by the new addition John Kitzmiller, who earned the nickname “The Flying Dutchman.” Kitzmiller took over the reigns as quarterback, moving Robinson full-time into the backfield alongside Williams.

With Kitzmiller passing the ball to Williams and Robinson, Oregon put together a 9-2 campaign, succumbing to both Stanford and Cal. It was the first time in school history that nine wins had been reached; a feat that would only be surpassed 70 years later when Oregon racked up 10 victories in 2000.

Despite the victories, and despite having Kitzmiller as the “acceptable” face of the program, many boosters and people in the community objected to Robinson and Williams being on the field at the same time. After conflicts with the administration, Coach McEwan grudgingly adhered to their demands.

“The coach finally made a compromise,” Brame said in the documentary The Forgotten Ducks (The Story of Charles Williams and Robert Robinson). “He wouldn’t start both of them here at home in Eugene or in Portland, but on the road, he would start them both.”

Robinson and Williams persevered through it all. Even though some in the stands booed and threw items at them and racist referees made calls against them, expectations were high for the 1929 season.

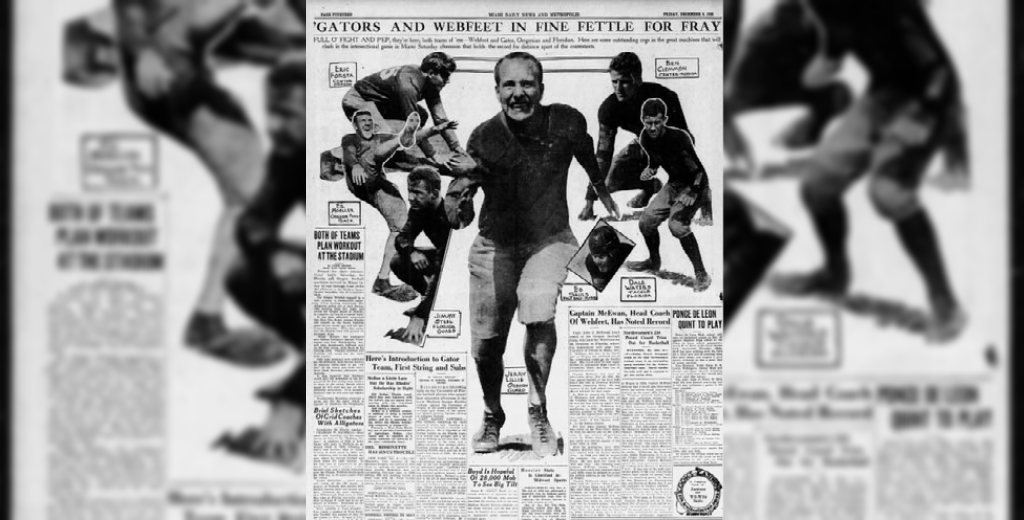

With the trio on the field, many thought that the Ducks could win the Pacific Coast Conference title; earning a trip to the Rose Bowl. Alas, they could not get past Stanford, racking up a 6-1 conference record heading into the last three games of the season vs. Hawaii, St. Mary’s, and Florida.

Worse still, Kitzmiller had fractured his ankle the week prior in the game against Oregon Agricultural College – OAC (now Oregon State), though the Ducks had managed to end their three-game losing streak to the hated OAC with a 16-10 victory in the rivalry game.

A disappointing end

Photo courtesy of Newspapers.com

Photo courtesy of Newspapers.com

With Kitzmiller out for the rest of the season, Robinson and Williams led the team through the final three games. The team beat Hawaii at home, thanks to an impressive defensive effort, but the Webfoots suffered a loss to St. Mary’s, a powerhouse at the time given the nickname “the Notre Dame of the West.”

Licking their wounds, Oregon traveled cross-country for the final game of the season to play the Florida Gators in Miami.

Robinson and Williams had carried the team for three years and were vital pieces in Coach McEwan’s attack. And, with Kitzmiller out of commission—along with four other players—the duo was essential to the team’s success.

The University of Florida, however, had a strict policy in place: no Black athletes allowed.

“The University of Florida wrote to the U of O and told them that they understood they had two African American athletes on the team and told them that if they brought them, they wouldn’t play,” Brame said in The Forgotten Ducks documentary.

In a low moment in UO football history, the administration reluctantly agreed to leave Robinson and Williams behind in the last game of their senior season. The duo was bitterly disappointed, and countless fans from the Oregon community were livid.

Williams recalled the experience in a 1974 interview with the Register Guard, “While the team was gone on that trip, Bobby and I went to Portland,” Williams said. “I happened to meet the mother of one of our White players on the street [and] she was so mad about what had happened that she was hoping Oregon would lose.”

And, without their star players, Oregon fell to the Gators, losing 20-6.

With their football careers over and their scholarships expired, Robinson and Williams left Eugene to pursue a life outside of football. After a few years in Los Angeles and competing in Canada in pole-vault, Robinson returned to UO to get his degree in physical education in 1935. He eventually settled in Los Angeles where, in his later years, he became a social activist.

Williams completed four years at the UO, however but did not earn a degree. He returned to Portland where he married and worked for the state for more than three decades.

Opening doors for student-athletes of all backgrounds

The dedication and efforts by Robinson and Williams paved the way for generations of Black athletes to shine at the university. For the present and future accomplishments yet to happen at the UO, a debt of gratitude is owed to these two who overcame adversity to be on and off the field.

Today, student-athletes of all backgrounds compete at the UO and the only colors that matter are green and yellow.

Editor's Note: This article was rewritten by Rayna Jackson, BA ’04 (Spanish), communications director for the UO Alumni Association. The original article and others like it can be found at FishDuck.com in FishDuck.com, in their history section.

Related Articles

The Oregon Mascot, Part 1: The Webfooter Years

The Oregon Mascot, Part 2: Becoming the Ducks

Black History at the University of Oregon | Herman Brame

Racing to Change: Student Life in the 1960s with Herman Brame

‘Black history is not a Black club. It's history.’

Eugene Register Guard – Dec 1, 1974 (page 40-41)

Oregana 1930