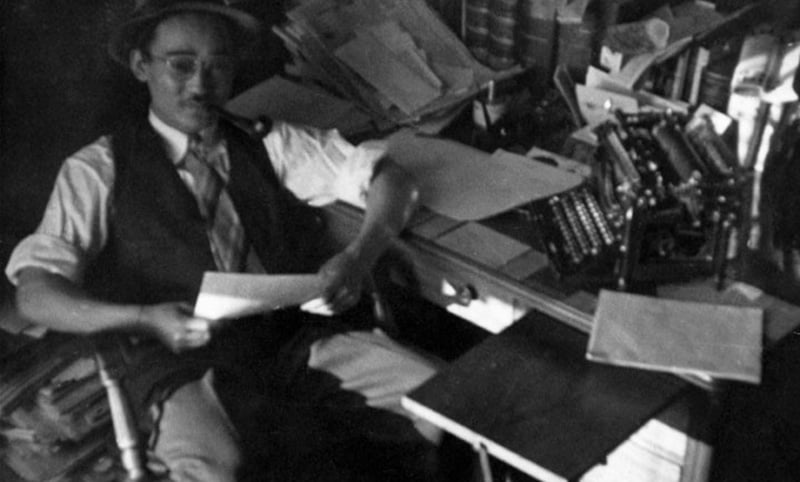

Minoru Yasui in his law office in Chicago, 1940.

Minoru "Min" Yasui, BA '37 (law), BL '39, dedicated his life to fighting for truth, justice, and the American way.

For that—and because of where his parents were born—he was placed in solitary confinement for nine months before the United States government sent him to a concentration camp.

But Min Yasui had the final word: not only was his conviction eventually reversed, he received the Presidential Medal of Freedom to show for it.

~ ~ ~

In 1903, 16-year-old Masuo Yasui moved to the United States from Japan. He worked on the railroad in Montana for a while, then moved to Portland to study English. In 1906, he borrowed money from his brother Renichi to begin buying inexpensive clear-cut land in Hood River, which he converted into farmland and orchards.

Oregon’s famous "fruit loop," the 35-mile stretch of the Hood River Valley filled with vineyards and orchards overflowing with apples, pears, and more, was in large part established by Yasui. His orchards were among the most productive in Oregon, and he was the first Japanese person ever elected to the Hood River Valley Apple Growers Association’s board of directors. He also provided financial assistance to the local Japanese community, helping them buy land of their own.

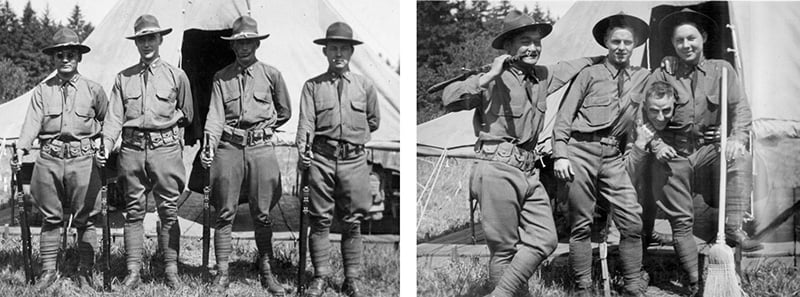

At the age of 26, Masuo married childhood sweetheart Shidzuyo Miyake, and the couple worked in their fields and orchard while raising nine children. The Yasui children enjoyed the quintessentially "All American" childhood on the banks of the Columbia River, participating in Boy Scouts and climbing Mount Hood to plant a USA flag at the summit.

Min (age five, holding the US flag) with his brothers and father while climbing Mount Hood.

Masuo was an admirer of Abraham Lincoln and always wanted to study law. However, as a Japanese immigrant he was barred from becoming a US citizen and as such was also barred from becoming a lawyer. Instead, he encouraged third-oldest child Minoru "Min" Yasui—who established the Mid-Columbia Japanese American Citizens League (JACL) at 14 and served as its president until he graduated from Hood River High School as the school’s salutatorian at 16—to practice law instead.

So, Min enrolled at the University of Oregon to do just that.

Min lived in Alpha Hall, part of Straub Hall, and played chess and cards with his classmates. He was active in ROTC, and was commissioned second lieutenant. Min was a member of the national Phi Beta Kappa honor society and earned a BA in law in 1937, and in spite of one Law School professor who made his life difficult due to his dislike of Japanese Americans, Min earned a bachelor of law in 1939 and passed the Oregon Bar that year.

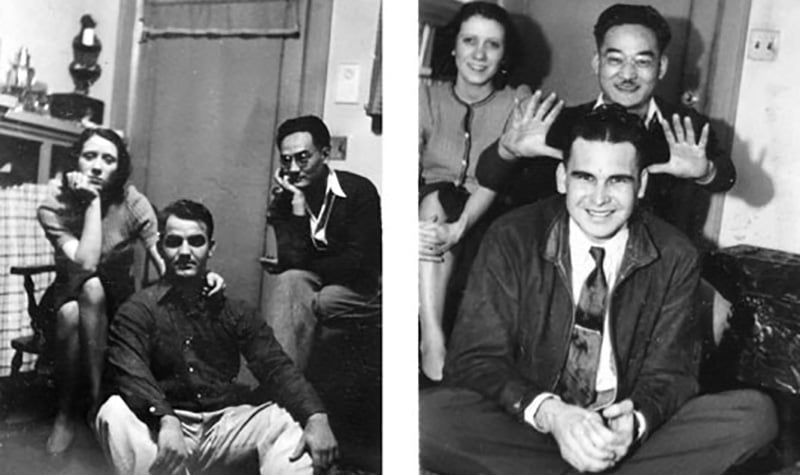

Min with college friends Dorothy and Demos, circa 1937.

But while Min was immersed in his textbooks in Eugene, it was events happening thousands of miles away that ended up shaping his future.

The year Min earned his first degree from the UO, an exchange of gunfire between Chinese and Japanese forces in Beijing led to the Second Sino-Japanese War. The year he earned his second degree from the UO, Nazi Germany invaded Poland, starting World War II. With skirmishes occurring between the Japanese and the Soviet Union along the border separating China and the Soviet Union, the Soviets allied themselves with China; in 1940, Nazi Germany formally allied itself with Italy and Japan.

And then came December 7, 1941. Shortly before 8:00 a.m. in Hawaii, more than 300 Imperial Japanese aircraft bombed the US naval base in Pearl Harbor, killing more than 2,000 and wounding a further 1,000. The United States declared war on Japan immediately, and three days later declared war upon Germany and Italy as well, fully joining World War II.

The day after the bombing of Pearl Harbor, the Treasury Department froze the bank accounts of all Japanese Americans, including those of Masuo Yasui. Several days later, he was arrested by the FBI, who told the family that their father—a pillar of the community who had lived in the United States most of his life—was potentially a dangerous enemy alien. The evidence used against Masuo included an award he had received for improving Japanese-American relations, and a map of the Panama Canal one of the Yasui children had drawn as part of a school project. The family wasn’t told where Masuo was being taken, and only found out later he had initially been sent to Multnomah County Jail, then to military prisoner of war camps in Montana, Oklahoma, Louisiana, and New Mexico. He was not released until 1946, the year after the war ended.

In February 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, which authorized the military "to exclude and remove any and all persons deemed necessary for securing the safety of the West Coast." In March, General John DeWitt, military commander of the Western Defense Command, issued Public Proclamation No. 3, which established an 8:00 p.m. curfew for German and Italian enemy aliens and all persons of Japanese ancestry, and confined them to an area within five miles of their homes. Then, in April and May, DeWitt ordered Japanese Americans to register and report to "assembly centers," which were temporary detention centers where they were imprisoned while the government set up 10 concentration camps in California, Arizona, Colorado, Utah, Idaho, Wyoming, and Arkansas. In all, more than 120,000 Japanese Americans were imprisoned in these camps and other detention centers during the war.

In May 1942, Shidzuyo and her two youngest children, Homer and Yuka, were placed on a train and sent south, without being told where they were going. In addition to leaving their home and possessions behind, they were also forced to abandon the family pets. Nobody wanted to adopt Nicodemus the cat and Mike the dog because, as Yuka would later say, "they had Jap blood." The shades over the train’s windows were lowered so nobody could see where they were going, but as it passed through Eugene, someone opened the shades enough to peek out. Michi, one of the Yasui siblings who was at the UO studying English in the hopes of becoming a teacher, was outside waving at the train as it went past. Shidzuyo remarked to Homer and Yuka that that may be the last time they ever see their sister.

Yasui family portrait. Standing, L-R: Younger brother Shu, friend of Min, Min, younger brother Homer, friend of Ray Tsuyoshi, younger brother Roku. Seated, L-R: Aunt Matsuyo, sister Michi, sister Yuka, mother Shidzuyo, father Masuo, older brother Ray Tsuyoshi, uncle Renichi.

Shidzuyo, Homer, and Yuka were taken to the Pinedale detention facility near Fresno, California, where they had to make their own hay-filled mattresses to sleep on, and where they shared doorless outhouses with snakes and scorpions. After several months at Pinedale they were moved again, and headed to Tule Lake—a concentration camp near the Oregon-California border that held, among thousands of other Japanese American prisoners, actors George Takei (Star Trek) and Pat Morita (Happy Days, The Karate Kid), and future Medal of Honor recipient James Okubo. Like all American concentration camps, Tule Lake was surrounded by barbed wire, and armed guards and dogs patrolled the perimeter around the clock.

Michi, meanwhile, finished her studies at the UO, but when it came time for her to graduate in 1942, found she was unable to attend her own commencement ceremony. The university scheduled the ceremony for 8:00 p.m.—when curfew took effect—and the army would not grant Michi an exception to attend. Robert Yasui, Min and Michi’s younger brother, was studying pre-medicine at the UO, but when he heard rumors of the forced evacuation, he moved to Denver and implored Michi to join him. On the evening of the UO’s graduation ceremony, while her classmates were donning their caps and gowns, Michi quietly packed up her belongings and boarded a bus for Colorado, which was outside of the military's Exclusion Zone.

At the time of the Pearl Harbor attack Min was almost 2,000 miles away from Oregon, working as an attaché at the Japanese Consulate in Chicago.

"He was shocked and horrified by the surprise attack on Pearl Harbor and immediately resigned from his job at the Japanese Consulate because he was an American," said Holly Yasui, Min’s daughter (the emphasis on "American" is hers). "There was absolutely no question in his mind that the Empire of Japan was the enemy of the United States, and of course he could not work for the enemy."

Min, an officer in the US Army’s Reserve Corps, returned to Oregon and attempted to enlist to fight for the United States, but was turned away due to his Japanese ancestry. So he put his UO law degree to use, and as the only attorney of Japanese ancestry in Oregon began helping Japanese Americans file legal paperwork to protect their property and help them comply with government regulations.

Then, he put his personal and professional futures on the line: If he couldn’t go to war to fight for the US, he was going to go to war to fight for democracy and justice against Public Proclamation No. 3.

Min during UO ROTC training, 1936.

At 8:00 p.m. on March 8, 1942, Min left his office in Portland and spent three hours looking for a police officer who would arrest him for breaking curfew, but none would. His secretary called police headquarters periodically to update them on Min’s whereabouts in case they wanted to arrest him, but her calls were ignored.

"I walked for over three hours," recalled Min in an interview featured in Never Give Up!: Min Yasui and the Fight for Justice, a documentary directed by daughter Holly and narrated by George Takei. "I had my birth certificate with me that proved that I was a person of Japanese ancestry. I asked [a police officer] to arrest me and the officer said, ‘Look, you’ll get in trouble. Go on, run along home.’ That certainly didn’t serve my purposes. So I went down to the Second Avenue police station and talked to the sergeant and explained what I wanted done. The sergeant obliged me and he threw me into the drunk tank."

Min remained in jail for three nights before being released on bail the following Monday. While he was in jail, the Oregonian ran a story about him headlined "Jap Leader Here Paid by Tokyo," and said he had been "exposed" by the FBI and was working with the Japanese government.

When Japanese Americans were ordered to evacuate Oregon several weeks later, Min informed the police that he was not going to follow orders he considered "unconstitutional, illegal, and unenforceable," and returned to Hood River instead. On May 12, military police showed up at the Yasui family home, arrested him, and took him to the North Portland Livestock Pavilion—which had been renamed the "Portland Assembly Center" but was still very much a livestock holding area—and he was kept in an animal pen with 3,600 other Japanese American prisoners beneath the watchful eye of armed sentries with searchlights in watchtowers.

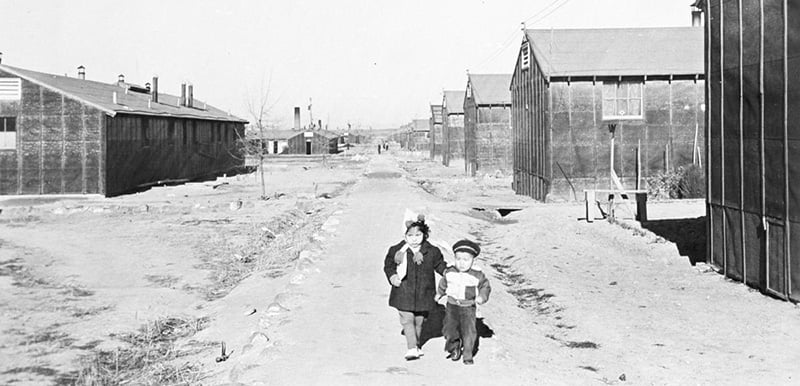

Min’s trial for violating curfew was held at the US District Court for Oregon and lasted only one day, but he had to wait five months before the judge ruled on his case. During this time he spent three months at the Portland Assembly Center, then a further two months at the Minidoka War Relocation Center in Idaho.

Two children in the Minidoka concentration camp, circa 1943. Photo courtesy Wing Luke Asian Museum.

In November 1942, the court ruled that the curfew was unconstitutional for US citizens, but applied to aliens. However, they also ruled that since Min had worked for the Japanese consulate he had forfeited his US citizenship, and was therefore an alien. He was found guilty and sent to the Multnomah County Jail, where he was kept in solitary confinement for nine months. It was four months before he was even allowed to shave or trim his fingernails.

Min asked for a typewriter so that he could keep in touch with family and friends, but his request was denied. "They wouldn't give me a typewriter because they thought Japanese were so clever that I'd fashion some kind of key or a weapon out of it," he later recalled. The jailers did, though, eventually give him paper and a pencil, so he could correspond with people.

"Christmas Day in jail," he wrote in a letter to Yuka on December 25, 1942, while he was in solitary confinement and his sister was at the Tule Lake concentration camp. "It's the first Christmas I've ever spent in jail, and I guess it's the first Christmas that you have ever spent behind barbed wire fences just like a herd of cattle."

Min appealed the District Court's decision to the Ninth Circuit, and while he languished in solitary confinement in Portland, the appeal went all the way to the Supreme Court. On July 21, 1943, the Supreme Court unanimously ruled in Yasui v. United States that requiring citizens to obey curfew during wartime was constitutional as a "military necessity," and allowed the District Court to rule on Min’s punishment. The District Court stated that Min’s time served at the Multnomah County Jail was enough, and released him—right back to the Minidoka War Relocation Center.

"He always emphasized the injustice and the humiliating conditions, such as being stuck in livestock stalls in the Portland "Assembly Center," the primitive conditions at the Minidoka "Relocation Center," where they had to deal with shoddy construction that let in heat, cold, and dirt through the cracks; overcrowding; lack of privacy; and exposure to the elements," said Holly. "He never spoke of how he was treated as an individual, but always talked about how the Japanese American community as a whole was subjected to great indignities and deprivations."

While Min was imprisoned the US Army had established the 442nd Infantry Regiment, a fighting unit composed entirely of Japanese American soldiers. Min attempted to enlist with the 442nd, but the army turned him down—this time because he had a criminal record.

(Min was later named an honorary life member of the 442nd, recognition that Holly said meant a lot to him—"It’s the only award that he typed in all caps in his curriculum vitae," she recalled.)

In the summer of 1944 Min was released from Minidoka on permanent leave and was allowed to return to Chicago. After a brief stint there, Min moved to Denver where his mother and sisters were living. He studied for the Colorado bar, and passed the bar exam with the highest score recorded that year. The following year, in 1945, he married True Shibata.

"It was only [after passing the bar exam] that I decided I could ask your mother to marry me, because before that, I was just an ex-con," Min once laughed to Holly.

The years following the war were not good ones for the Japanese American community on the West Coast. Former Oregon governor Walter Pierce said "We should never be satisfied until every last Jap has been run out of [the] United States and our Constitution changed so they can never get back," and the Emerald ran columns questioning the allegiances of the newly returned students. Yuka, BA '48 (biology), was one such student, but when she graduated from the UO she was not listed in the Oregana alongside her fellow graduates.

In Denver, Min became a legal aid lawyer who took on so many cases pro bono that his secretary had to remind him to charge for his work. He helped immigrants and low income people navigate bureaucratic rules and regulations, helped settle Japanese war brides who had married US soldiers during the war, put his Spanish skills to the test helping Mexican immigrants, and filed thousands of claims under the Japanese American Evacuation Claims Act of 1948 to help Japanese Americans get compensation for the losses they had incurred under Executive Order 9066.

"There are still a number of four-drawer file cabinets full of these filings in the basement of our family home in Denver," said Holly.

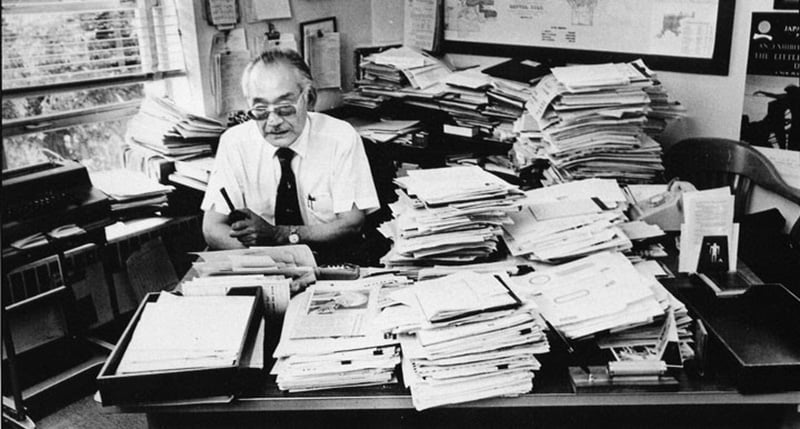

Min in his office in Denver, 1983.

Min had a seemingly endless supply of energy and drive. He served as scoutmaster of a multiracial Boy Scout troop. He helped found the Urban League of Denver, an African American community organization. He was an officer in the Mile-High JACL and Intermountain District of the national organization, and lobbied for the passage of the McCarran-Walter Act of 1952, which allowed Japanese immigrants to apply for US citizenship—Masuo and Shidzuyo, who moved to Portland after the war but never set foot in Hood River again, both became citizens after the Act passed. He helped found the Latin American Research and Service Agency. He helped organize Denver Native Americans United. He became a member of the National Association of Police-Community Relations. He was a member of the National Association of Human Rights Workers. He was the chair of the National JACL Committee on Redress, which was the main cause he fought for over the remainder of his life.

But he also wasn’t finished taking on the US Government.

On February 1, 1983, Min’s lead attorney Peggy Nagae—who was also the assistant dean for academic affairs at the UO School of Law—filed a writ to have the US District Court reopen Min’s original case. Min wanted the court to vacate his conviction, dismiss the indictment, and hold an evidentiary hearing and find:

1. that there was no "military necessity" for the curfew, exclusion, and internment

2. the policy was racist and the decisions made were based on racism

3. that the government knew and withheld evidence refuting the "military necessity" claim

A judge vacated Min’s conviction on January 26, 1984, but dismissed the remaining allegations. Undeterred, Peggy and Min appealed the decision—they were determined to have an evidentiary hearing and establish that there had, in fact, been governmental misconduct.

"The judge said we didn’t need to have an evidentiary hearing, and that was a large point of why we wanted to do this—so that people could see the documents that said the incarceration was based on race and racism and that the government withheld exculpatory material from the U.S. Supreme Court," said Nagae, whose own father was also imprisoned at Minidoka and years later told her he was still bitter about it.

Among the many key reports Nagae and Min's team cited was one of particular importance. Aiko Yoshinaga Herzog, a Nisei (person born in the USA to Japanese parents) researcher for the Commission on Wartime Internment of Civilians, found a first draft of DeWitt’s final report, in which he wrote, "the Japanese race is an enemy race," and no matter how much time you took, you could not "separate the sheep from the goats." Therefore, according to DeWitt, locking them all up was necessary. The United States government had quietly removed the proof of racial basis for Public Proclamation No. 3 and the entire evacuation and relocation policy, and instead presented it as a "military necessity."

Minoru Yasui died on November 12, 1986, while his case was on appeal to the Ninth Circuit, and was buried in his hometown of Hood River. Both the Ninth Circuit and the Supreme Court dismissed the appeal. To them, Min’s death meant the case was moot.

Two years after Min’s death, President Ronald Reagan signed the Civil Liberties Act of 1988 into law, granting redress and formally apologizing to every Japanese American incarcerated during WWII. In 2002, the University of Oregon Law School presented Min’s widow True with a Meritorious Service Award, and established an endowed chair in support of human rights—the first in the nation to be named for a Japanese American. The city of Denver named a building after him—the Minoru Yasui Plaza, which has a bust of Min on display in its lobby. The Minoru Yasui Community Volunteer Award is given to outstanding volunteers in Denver each year, and he was named one of the city's Millennial Award recipients in 2000. His home state of Oregon honored him with Minoru Yasui Day, held on March 27.

Meanwhile, Peggy Nagae and the legal team that worked on Min’s case in the 1980s continued fighting for justice, submitting briefs in cases where Muslims were racially profiled following 9/11, another challenging the New York Police Department’s surveillance and racial profiling of Muslim Americans, and more still challenging the National Defense and Authorization Act, which authorized attribution of guilt by association and indefinite detention—concepts that were used against Japanese Americans during World War II.

Laurie Yasui receiving Min's Presidential Medal of Freedom from President Barack Obama. Photo courtesy the White House.

In 2014, Peggy Nagae and Holly Yasui co-founded the Minoru Yasui Tribute Committee to nominate Min for a posthumous Presidential Medal of Freedom, the nation’s highest civilian honor. On November 24, 2015, Min received the award, and President Barack Obama presented the medal to Laurie Yasui, one of Min’s daughters, during a ceremony at the White House. The boy from Hood River who grew up to spend his life fighting for justice, and who once remarked that "what is done to the least of us can be done to all of us," became a member of a rarified group that includes such distinguished figures as NASA mathematician Katherine Johnson, disability rights activist Helen Keller, the crew of the Apollo 11, Civil Rights icons Martin Luther King Jr. and Rosa Parks, Cherokee chief Wilma Mankiller, and Reader’s Digest founder and UO alumna Lila Wallace, BA 1917 (German).

"I wished he were alive to go to the White House to receive the Medal of Freedom from the first Black President in our nation’s history," said Holly. "My dad was, above all, deeply patriotic, so I think he would have considered the Presidential Medal of Freedom a crowning achievement in his life. He received many awards during his lifetime since he was active in so many areas, but I think he would feel vindicated that all his life’s work, all the millions of hours he spent fighting for justice on behalf of the oppressed and disenfranchised, was recognized and appreciated by the President of the United States."

The cell in which Minoru Yasui spent nine months in solitary confinement in the Multnomah County Jail is now on display in the Japanese American Museum of Oregon in Portland. To date, Minoru Yasui is the only Oregonian to receive the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

- Damian Foley, UO Communications. Photos courtesy Holly Yasui unless otherwise indicated.