Tinker Hatfield on the Black Duck and allyship

Legendary sprinter and designer Tinker Hatfield, BArch ’77, talks about what it means to be an ally, creating the Black Duck, and how his time at the UO impacted how he sees the world.

HEN SOMEONE MENTIONS the name Tinker Hatfield, there is immediately a long list of accomplishments that come to mind.

Sneakerheads know him for his work designing the original Air Max cross training shoe in 1981 and the collaboration with Michael Jordan on the world-famous Air Jordan line.

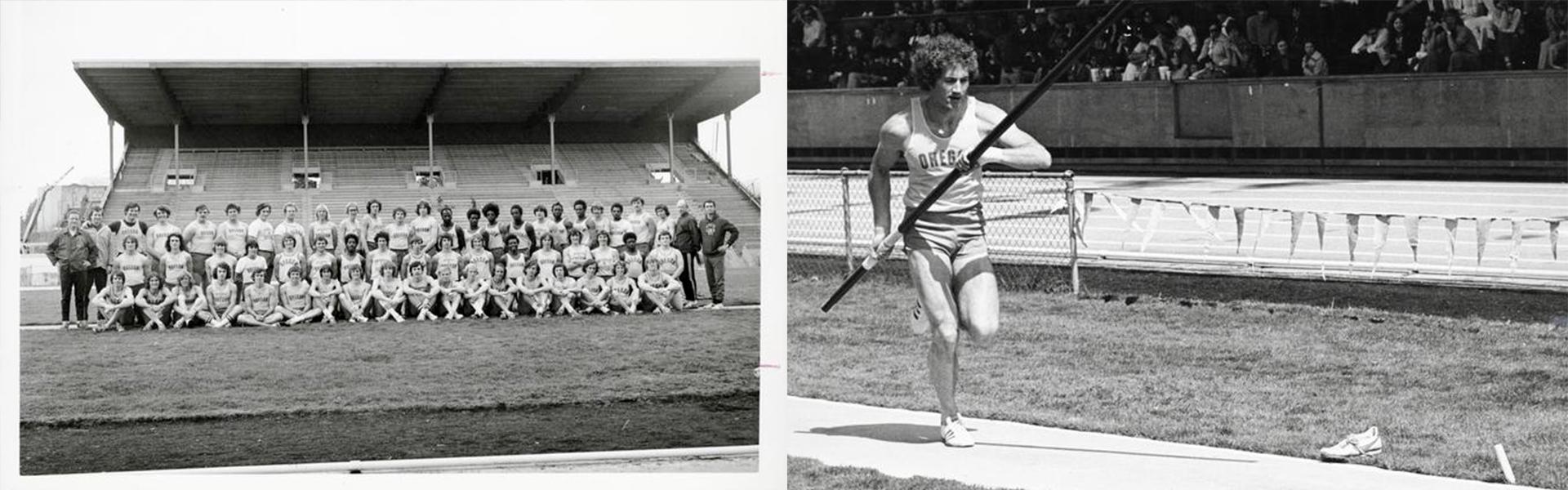

Track enthusiasts may point to his track and field career under legendary coach Bill Bowerman where he held the pole-vault record for the university and finished sixth in the 1976 U.S. Olympic trials.

And Duck loyalists can single out his contributions to the University of Oregon which include the creation of the inspired design for the Matthew Knight Arena floor as well as having an integral role in designing the iconic “O” logo.

He was named one of the 100 Most Influential Designers of the Century by Fortune Magazine in 1998 and earned a place in the Oregon Sports Hall of Fame for Special Contribution to Sport in 2008.

But this fall, Tinker Hatfield added one more accolade to his long list when he received the Duck Legends Ally award from the UO Black Alumni Network (UOBAN). This inaugural award recognizes an ally (or organization) who exemplifies an unwavering commitment to diversity, equity, and inclusion.

In particular, the award honors an ally who has taken on the role of champion and advocate of Black students and the community. It also looks at an individual who actively promotes and aspires to advance a culture of inclusion through purposeful, positive, and mindful efforts that benefit the Black community.

“I just try to do the right thing, and I'm not always successful. But all you can do is try. And more often than not, if you try hard enough, you can make a difference.

”

“I can't tell you how important it is for me to give back when I can and to initiate a certain level of understanding and compassion and to push for change,” Tinker says. “That's just a part of what I do.”

In this interview with Meredith Lancaster, MA ’15 (art history), member of the UO Black Alumni Network, Hatfield shares how being an ally isn’t just about graphic design, a logo, or a piece of art, but rather supporting people in a variety of ways through genuine friendship and mentorship.

With the latter, few may know that Hatfield gives his time and money to support CHAMPS Male Mentoring program in Chicago. The program serves to educate, empower, and expose boys and young men of color beyond school to help them achieve their dreams and goals.

“I have spoken to small groups of 15 to 2,000 kids at a time,” says Hatfield. “More importantly, I listen and I pay attention.”

But Hatfield admits, he doesn’t always get it “right.”

“I’m friends with Spike Lee, and his film Do the Right Thing is one of my favorite movies and is at the center of my life,” says Hatfield. “I just try to do the right thing, and I'm not always successful. But all you can do is try. And more often than not, if you try hard enough, you can make a difference."

Hatfield also shares with Lancaster how his experiences at the UO, friendships with track and field teammates, and his mentorship under Bowerman have influenced his philosophy on life.

–Rayna Jackson, BA ‘04 (romance languages), UO Alumni Association communications director

MEREDITH: Let’s jump right in. How did the UO get on your radar, and what were some of the main draws that made you want to attend?

TINKER: Well, I'm from a small town in Oregon. But I developed into an athlete with a certain level of expertise and success and competed all over the United States. In high school, I did track and field, but I also was a pre-season American in football. And I was decent in basketball. So, I got recruited for different sports around the country. I visited a lot of schools in my junior and my senior year and regardless of the school – whether it was USC or Arizona State or Stanford, they would always ask me what I wanted to study and what I wanted to do after college. I had this notion, and I really didn't know too much about it, but I wanted to be an architect.

MEREDITH: And how did the coaches and schools respond to you wanting to study architecture?

TINKER: I'd say it was almost unanimous that the coaches would say something like, ‘We don't have architecture’ or ‘We're not so sure that we can give you the scholarship and bring you in as a division one athlete and be successful.’ ‘We're not so sure you can be successful in such a difficult or time-consuming major and be a division one athlete.’ Those were the standard answers. And then different coaches would ask me, ‘Well, would you consider another major?’ Of course, I said, ‘Yeah, I will consider it.’ And, then I would leave and do the next campus visit.

MEREDITH: It sounds like the UO was last on your list. How did you finally make it to campus?

TINKER: I only lived 25 miles from the campus, but my very last visit was to the University of Oregon. At the time, I was recruited by Columbia and was excited to see New York. I went to Los Angeles to be recruited by USC, and even the University of Kansas. I was excited to go visit them all.

When I was in my senior year in high school, I didn't know too much about the University of Oregon other than it was known as a track school. But I met Bill Bowerman, the legendary coach and founder of Nike, and he asked me the same question about what I wanted to study. He asked, ‘Well, have you prepared for architecture school?’ And I said, ‘Nope, I don’t even have a portfolio.’ And he goes, ‘Well, do you realize how difficult and time-consuming architecture is?’ And I said, ‘Yeah, I've been told.’ And he said, ‘Well, it's a difficult and challenging major, but you know what? I believe in people who step outside of their comfort zone and accept challenges.’ In fact, he was optimistic about me being successful at the University of Oregon.

His philosophy was to look beyond sports and beyond the notion that all we want to do is to have you come here and win. He said, ‘No, I want to build young people into contributors to society. And if architecture is your chosen major, we will give you the scholarship, and I will personally get you into the School of Architecture.’

That sealed the deal and about three or four weeks later, there was a press conference, and I revealed that I was going to the University of Oregon on a track scholarship because there was some speculation that I might go somewhere else for football.

MEREDITH: Let's talk more about the beginnings of your activism and the formation of your allyship. And just to set the scene, this is the early to mid-70s. There's a lot of turmoil not only in the world, but in the country and on campus as well. We're talking about the Vietnam War and the draft, war protests, uprisings, and takeovers. And while all of this is happening, you're leaving your home – your small farming community in Halsey and find yourself just sort of in the middle of it. What were some of the things that you encountered in your first few weeks and months on campus, and how did those moments inform your activism? And did you find yourself feeling the need to kind of get involved right away? Or was it more of a slow burn?

TINKER: That's a great question, but I have to set the stage by mentioning that even though I grew up in a small town and a small high school, I was competing all over the United States. And I had great friends from my high school days, traveling and competing with and against, and just hanging with athletes that didn't look like me.

For the first couple of years at the University of Oregon, my life revolved around architecture students, which wasn't a real diverse crowd, and then track athletes. And I was in the sprinters’ subculture within the track team. So, I guess you could say I was in the minority because most of the sprinters and jumpers were Black athletes.

MEREDITH: What insight and impact did being accepted by Black athletes have on you?

TINKER: It was very cool for me to be accepted by that crowd within the University of Oregon. I was not only just a part of that group on the track team, but I was also good enough to be competing at the highest level as a sprinter and a hurdler. I set the freshman record in the high hurdles. So, I wasn't just around it, I was really in the middle of it, and I really accepted that role.

I remember having a connection with athletes of color because I was around when John Carlos and Tommy Smith did the Black Power salute in the 1968 Olympics in Mexico City. I was very sympathetic to what they were trying to say and what they were trying to do, as was Bill Bowerman, who was an assistant coach for that Olympic team. They were stripped of their medals immediately, and Bill fought to have their medals restored. He was what I would call a progressive thinker, open minded, and his track team was diverse. He just didn't see the negativity of someone trying to make a statement. There were still a lot of issues around race and opportunity, and he was so much for the athletes and that really impacted me as a young athlete.

MEREDITH: How did this connection with the Black athletes lead to the creation of the Black Duck?

TINKER: The Black athletes knew I could draw because I was in the School of Architecture. It was my second year when a group of sprinters who were part of the Black Student Union asked me if I could design something that recognized the contributions of Black student athletes at the University of Oregon. I said I'd be honored to work on a symbol. And that's when I drew the Black Duck and the White Duck running across the finish line together. When I finished the drawing, I showed it to the athletes who had requested my involvement and they thought it was great. Then it went to Bill Bowerman and the rest of the track team – and there were about 90 athletes on the track team at the time. There was a vote: 90 to 0, to include this new logo on the actual competitive warm-up top that we all wore.

It was a bold and positive statement about diversity and Black contributions to not only the track team, but to the university at large. It was super cool for me to be involved in that.

“. . . diversity counts, diversity matters, and it’s what makes a strong education and a strong community.

”

MEREDITH: That's such a bold move for the coach and student athletes. You know, the first census of the Black student population was 1974. And at that point, there were only 1.4% Black students who made up the total population at the UO. It is remarkable that it happened, and that it was well received. Now, more recently, what made you want to revise and reintroduce the Black Duck?

TINKER: There's an interesting question. You know, we like to think that there's been a ton of progress since 1973 or 1974. And, in some ways there has been, and in some ways there hasn't.

A few years back, I spoke with the head track coach Robert Johnson who is Black. He asked me if I would reprise that logo and bring it back. And so, I had printed and embroidered it in a much larger patch. I'm not sure what happened, but it was never used by the track team. I don't know if it wasn’t approved or didn’t pass muster. But then, I started thinking that the logo was dated. At the time it was originally created, everybody I knew on the track team or at the University of Oregon who was Black had an afro. And I think that all these years later, it's become more of a stereotype than what I would call a statement of unique cultural differences. And so, because I've always been involved with diversity and it is part of my philosophy and worked with all kinds of people at Nike, I thought, ‘Well, what am I going do?’

I also want to point out that I had redesigned the Duck for the University of Oregon, which was to take Donald Duck and turn it into the Oregon Duck. And so, I was the one who came up with that idea, and I had a graphic designer polish it off for me. But having done that I thought, ‘Well, what if we start thinking about the Duck, which is typically White, and what if the Duck comes in all colors?’ And so, I started presenting and pushing for this sort of Andy Warhol approach to the Duck coming in all colors.

I wanted to take the Black Duck and start using that on shoes and on football uniforms. Our Black student athletes are extremely important to the success of these sports teams. And I should say the notion of diversity across the university is important and is growing, but it’s with the sports teams where we see it the most. Being in a position of some influence at Nike and at the University of Oregon, I managed to get that approved. The statement here is that diversity counts, diversity matters, and it’s what makes a strong education and a strong community.

MEREDITH: How do you see the Black Duck being used moving forward? What are your dreams for it? Do you want it to be on everything?

TINKER: It's been used now on limited-edition Air Jordans for the football team and for the basketball team. But I'd like to see it used intermittently with other sports teams and I'd also like to see it pop up in the bookstore and in the stores that sell University of Oregon merchandise. It's not like we can only [represent] the White Duck or Black Duck. The Duck can represent Native American, Latino, and Asian students – there are so many different people that make up the UO, and this could become a forward-thinking statement from the university that diversity makes the world go around. It makes communities, organizations, and universities better – and more fun too, for that matter.

MEREDITH: This has been such an enjoyable interview – and we really have been able to see how you strive to be a good person and be an ally in everything that you do.

TINKER: Thank you, I appreciate it. I just want to share one more thing. Michael Jordan’s nickname is “Black Cat,” so for his birthday I drew him a card that has a black cat on it. He called me and said it touched him, and then he said, ‘I love you, brother.’ And I think it's meaningful to be considered not just white or black or any color, but in this case, to be a brother. I’m friends with a lot of people, but everything is a two-way street, we help each other out and that's how good things happen.