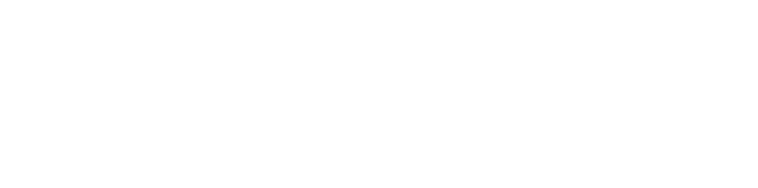

Nancy Welborn featured in the Amateur Softball Association's magazine.

Legend of the game: the Nancy Welborn story

While helping my dad, Roger Becker and his wife, Kathleen Welborn Becker move, I found a box of my stepmother’s family memorabilia. Among the glossy black-and-white photographs of smiling children, yellowed birth announcements, and faded wedding invitations was a bright, colorful game program for a women’s softball team called the San Diego Sandpipers. I was immediately curious and asked why she kept the program from half a century earlier.

“The Sandpipers were the team my sister Nancy played for,” Kathleen said. “Nancy was one of the greatest softball players of all time.”

It was easy to dismiss my stepmom’s enthusiasm for her sister’s athletic skills as uninformed family bias. But I could not get over the fact that there had been a professional sports team I had never heard of with players who had apparently been overlooked by later generations.

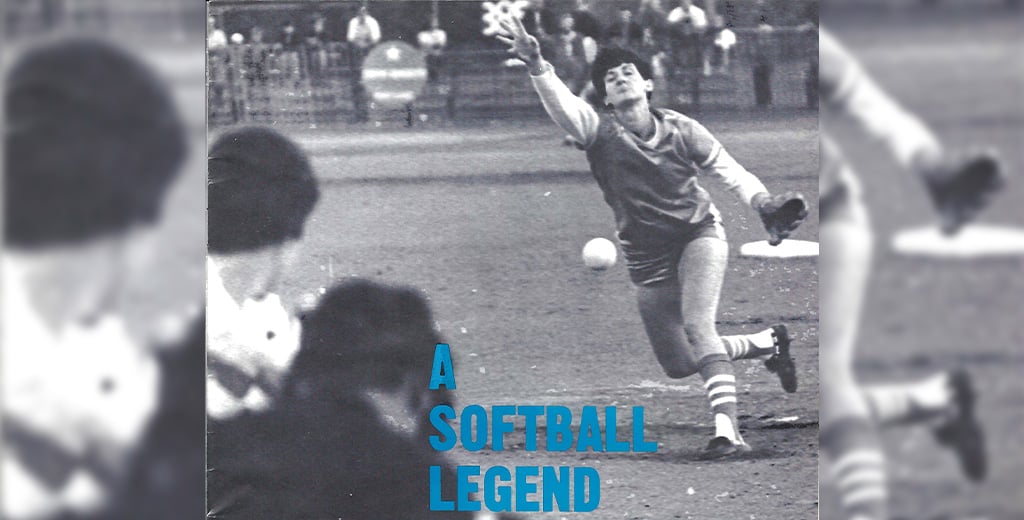

Nancy Welborn is pictured at bat in a player profile from the 1973 Orange Lionettes program.

My curiosity was piqued, and I began tracking down details on the San Diego Sandpipers and pitcher Nancy Welborn, BS ’70 (physical education). I discovered that the UO alumna was in fact one of the greatest softball players ever. I also found she started her career long before federal law mandated equal funding for women’s sports. She was just a teenager playing on a team in Eugene who had to overcome overt discrimination against female athletes and the tension of being a closeted lesbian at a time when being gay was illegal in many places and disapproved of most everywhere else.

Welborn, born in 1944 in Telluride, Colorado, learned early on that her gender excluded her from the organized sports activities she craved.

“There were no programs for girls who itched to throw, bat, run, and just see how we stacked up against the best of all the other kids,” Welborn said. “So we learned to embrace the label of tomboy and just join in the rare sandlot game or neighborhood test of skill.”

The lack of school-based sports programs for girls forced her to get creative. Her sisters were generally willing to play catch with her, at least until she started throwing the ball hard. Her uncle gave her a worn out, barely useable baseball mitt, which she used to practice.

“It was just an old rag, but that memory is still very clear in my mind,” she said. “How I loved that thing; I carried it with me all the time. It was a love I had from early on.”

By the late 1950s, the Welborn family was living east of Eugene in Westfir, Oregon. During a neighborhood ball game, Nancy was approached by a truck driver named Bo Willis. Willis, familiar to kids in the neighborhood as the man who delivered milk to their school, was also the coach of a men’s fastpitch softball team. He saw Nancy play and suggested she meet the coach of a women’s amateur softball team based in Eugene.

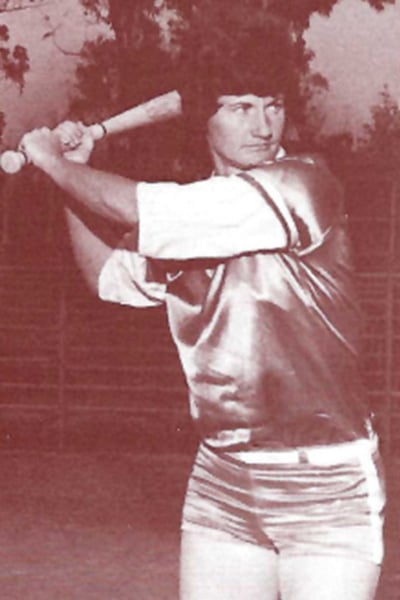

Nancy Welborn running the bases in Sun City, Arizona in the late 1970s. Welborn was a pitcher before the designated hitter rule went into effect. She had a lifetime batting average of .250.

At age 14, Welborn began commuting to Eugene to play for an amateur team sponsored by the local distributor for McCullough Chainsaws and managed by Jack Moore. She eventually moved in with her sister who had an apartment there.

By the time she was 16 or 17, Welborn had reached a pivotal moment in her life, a time she counted on her sister and her teammates to accept herself and her sexuality.

“Those were the years I began to understand I was gay,” Welborn said. “It was especially difficult since I knew my parents definitely would not approve, and you don’t want to disappoint your parents, so stuff like that forced me to stay closeted. The benefit of being on a team is sharing these kinds of struggles with your teammates and you deal with them together.”

During her time on the McCullough Chainsaws women’s team, Welborn developed into a skilled pitcher. As her ability to outsmart batters grew, the “Saws” began to win. By 1965, they won their first regional championship and traveled to Connecticut where they had their first exposure to elite softball competition. In a tournament with 30 to 40 teams, the McCullough Chainsaws finished fifth in 1965 and sixth in 1966.

“It gave me a taste of that sort of success and that sort of notoriety,” Welborn said. “I got to watch some of the really elite athletes and decided that was what I really wanted to do.”

Nancy Welborn (pictured fourth from the left in the back row) alongside her teammates on the 1973 cover of the Orange Lionettes program.

In 1969, at age 24, Welborn left Eugene to join the Orange Lionettes in Southern California, becoming part of an established squad that had won the national title the year before. It featured a talent-filled roster and coach Shirley Topley, who would go on to coach the gold-medal winning US softball team at the 1996 Olympic Games.

The Lionettes won National Amateur Softball championship titles in 1969 and 1970, with Welborn as their pitcher. This qualified the team to represent the US at the World Softball Championships that year in Japan, where they finished second. Topley said Welborn’s conduct both on and off the pitching mound was a huge contributor to the team’s success.

“Nancy was very humble and was devoted to her team which made her teammates want to work with her,” Topley said.

Welborn remained part of the Orange Lionettes for five more years and was a first-team All American every year from 1969 to 1973. In the mid-1970s, she moved to newly formed professional softball league, the San Diego Sandpipers, where her role included playing and coaching. Unfortunately, the league faced many business challenges and folded in the late 1970s.

Portrait taken of Nancy Welborn for her induction into the USA Softball Hall of Fame in 1982.

However, the confidence and focus Welborn acquired playing softball paid off in many aspects of her life. While playing softball, she earned her bachelor’s degree in physical education at the University of Oregon in 1970 and began teaching in Southern California that year. She later completed a master’s degree and became a high school counselor. Welborn was inducted into the National Softball Hall of Fame in 1982.

Today, she lives on a farm in Central Oregon with her partner Joanne, enjoying a peaceful retirement. Looking back, Welborn said she’s grateful for the experiences she shared with teammates in a time when women did not have the access to sports that they do today.

“This is not a poor me story. I feel very fortunate to have been exposed the way I was to people who were supportive and were skilled and wanting to transfer their knowledge on to us.”

-By Steve Becker